Concern heightens interest, but support propels change. Several questions on the IEA-P assessed whether the public’s concern over gifted education was strong enough to translate into active support for specific program provisions, including: (1) creating programs in areas traditionally underserved by gifted education, (2) allowing gifted students to accelerate, (3) creating separate schools for gifted students, (4) creating online schools for the gifted, and (5) requiring training for teachers who work with gifted students.

Public Support for Specific Provisions in Gifted Education

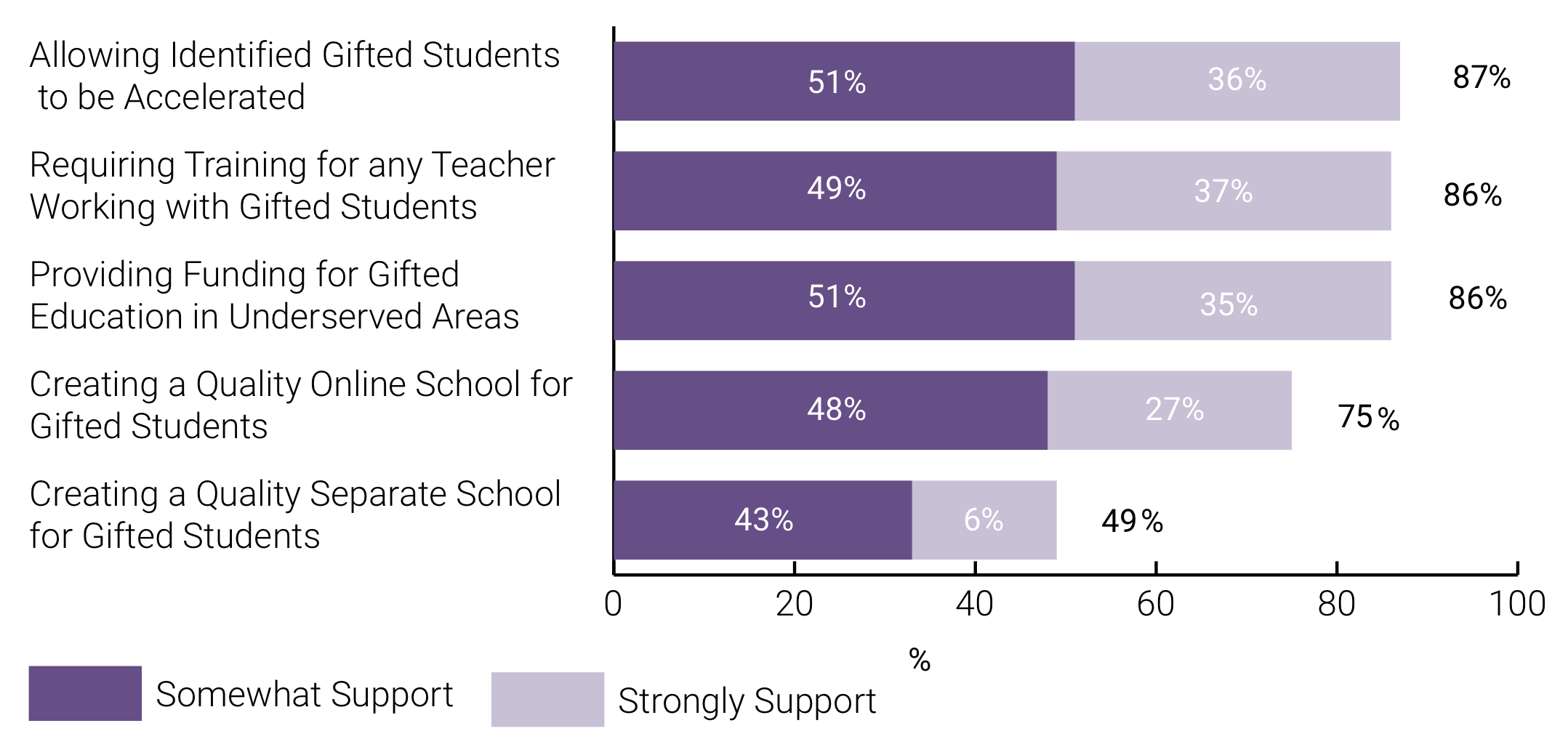

The public’s concern over gifted education was strong enough to translate into active support for specific program provisions. IEA-P respondents reported overwhelming support for each program provision included in the poll (Table 4.1, Figure 4.1). Providing gifted programs in underserved areas, requiring professional development for teachers who work with gifted students, and allowing gifted students to accelerate received almost identical levels of support, with 86-87% of respondents in favor of each option

Do you Support or Oppose…

Figure 4.1. Percentage of respondents who reported support for commonly recommended provisions for gifted students.

Percentage of Responses in Support for Program Provisions to Improve Gifted Education (Q36)

Notes. ±5.81% among Hispanics, and ±3.33 among Whites. Race/Ethnicity does not include respondents who selected more than one race. Race/Ethnicity x Income does not include respondents who selected “Prefer Not to Indicate.”

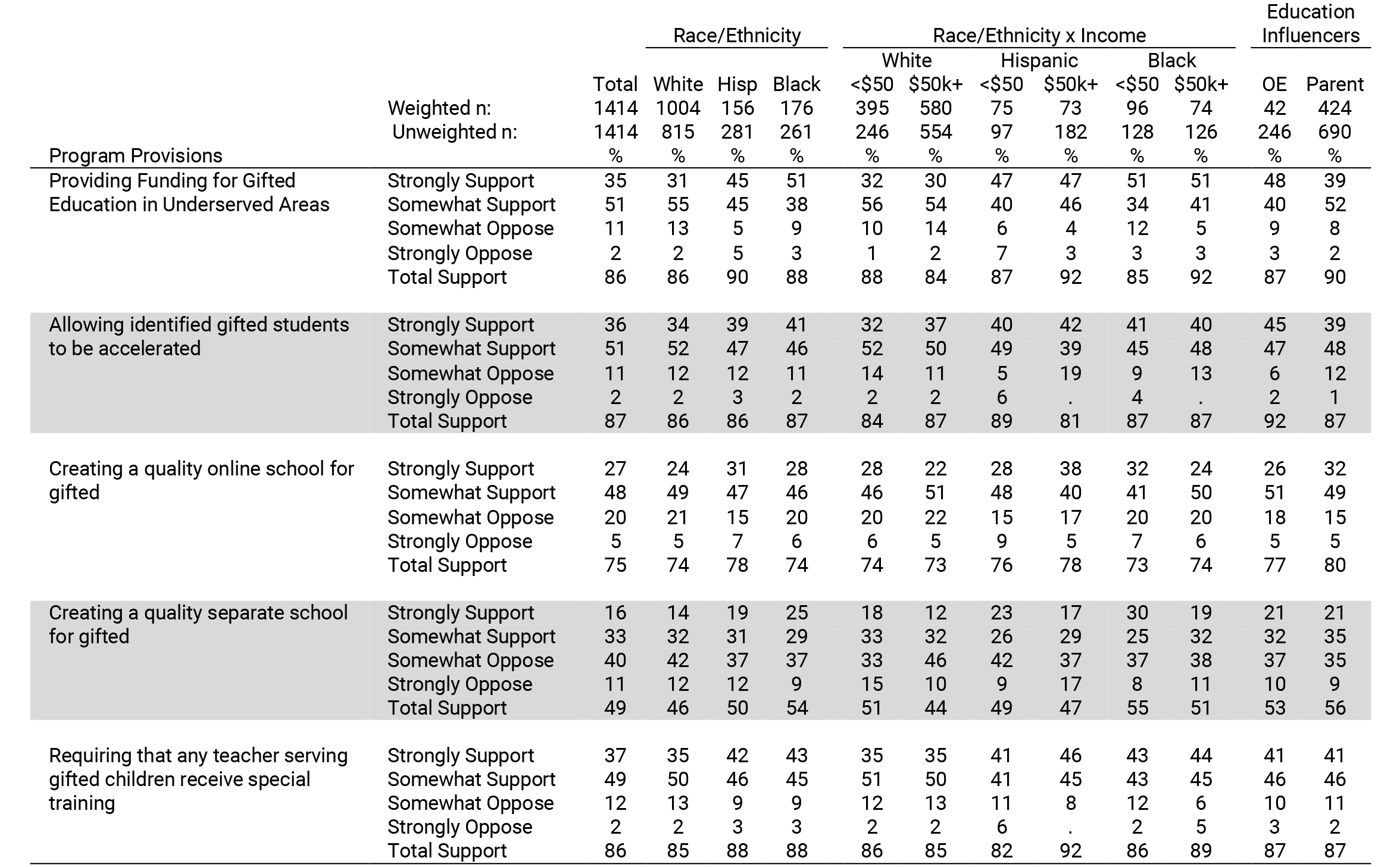

Providing funding for programs in underserved areas. An overwhelming majority of the American public supports providing funding for gifted programs in underserved areas. Fully 86% of IEA-P respondents gave support at some level, and 35% strongly support providing programs in underserved areas.

Education Influencers. Among Parents, 92% voiced support for providing programs for gifted students in underserved areas, as did 87% of Opinion Elites. “Strong” support was also high among Opinion Elites and Parents (48% and 42%, respectively).

Racial/Ethnic Groups. The level of support for providing programs in underserved areas ranged from 84% among higher-income White respondents to 92% among higher-income Hispanic and Black respondents (Figure 4.5). More disparity was observed in the number of respondents in each group who “Strongly” supported the idea. Consistent with previous poll questions, Black and Hispanic respondents were more likely to give strong support for establishing programs in underserved areas. Nearly half of Hispanic respondents (47%) and Black respondents (51%) offered strong support for establishing programs in underserved areas, regardless of income, compared to 31% of White respondents.

Allowing gifted students to accelerate . A vast majority of IEA-P respondents supported acceleration for gifted students, whether by grade skipping, ability grouping, or through other means. Overall, 87% expressed some level of support, and 36% strongly supported allowing gifted students to move ahead based on readiness rather than remaining in a lock-stepped age-based grade progression.

Education Influencers. Opinion Elites responded in favor of acceleration more frequently than any other group with 45% indicating strong support and 92% overall support. Support from Parents matched other subgroups, with 39% offering strong support and 48% responding they “Somewhat Support” acceleration.

Racial/Ethnic Groups. At least 80% of all subgroups supported acceleration for gifted students, and more than 32% gave strong support. The highest level of strong support came from Black and Hispanic respondents, 40-50% of whom indicated strong support regardless of income level. Lower-income White respondents were least likely to lend strong support (32%) but most likely to “Somewhat Support” (52%).

Establishing schools for the gifted. Among all IEA-P respondents, 75% responded favorably to establishing online schools for the gifted, and 27% offered strong support. The concept of establishing separate brick-and-mortar schools for gifted students received a tepid response relative to other program options, with support from just half of respondents (49%). The rate of support was at least 25% lower than the other four program provisions and 30% lower than acceleration.

Do you Support or Oppose Funding for Gifted Programs in Underserved Communities?

Figure 4.2. Percentage of respondents in support of providing funding for gifted programs in underserved communities, by race/ethnicity x income.

Education Influencers. Support for the concept of an online school for the gifted was equally high among Opinion Elites and Parents (77% and 80%, respectively). Fewer supported a brick-and-mortar school, consistent with the overall trend in the data. Only 53% of Opinion Elites and 56% of Parents supported the creation of a separate school for the gifted. Parents were far more likely to offer strong support for an online school (32%) than they were for a separate school for the gifted (21%).

Racial/Ethnic Groups. Higher-income Hispanic and lower-income Black respondents were enthusiastic about an online school, with 38% and 32%, respectively, giving the idea strong support. Higher- income White and Black respondents were least likely to offer strong support for an online school (22% and 24%, respectively).

Although they were the least popular in general, brick- and-mortar schools were not universally rejected. Black respondents were more likely to support online schools overall (74% total support for an online school versus 54% for brick-and-mortar), but similar percentages “Strongly Support” online (28%) and brick-and-mortar (25%) schools for the gifted. Lower- income Blacks in particular were equally likely to offer strong support to brick-and-mortar schools and to online schools (32% and 30% strong support).

Requiring specialized training for teachers who instruct gifted children. Over 8 in 10 Americans supported a requirement for teachers who work with gifted students to receive special training (86% total support, 37% strongly support, Table 4.1).

Education Influencers. Opinion Elites and Parents were equally likely to support required professional development for teachers working with gifted students. In each group, 87% reported they “Somewhat” or “Strongly” support the idea and 41% offered “Strong Support.”

Racial/Ethnic Groups. Well over 80% of all three racial/ethnic groups supported requiring specialized training for teachers who work with gifted children, including 85% of White respondents and 88% of Black and Hispanic respondents. Strong support was highest among higher-income Black (44%) and Hispanic (46%) respondents; strong support was somewhat lower among White respondents but still accounted for one-third of the subsample (35%).

The Impact of Words and Concepts on Public Support for Program Provisions

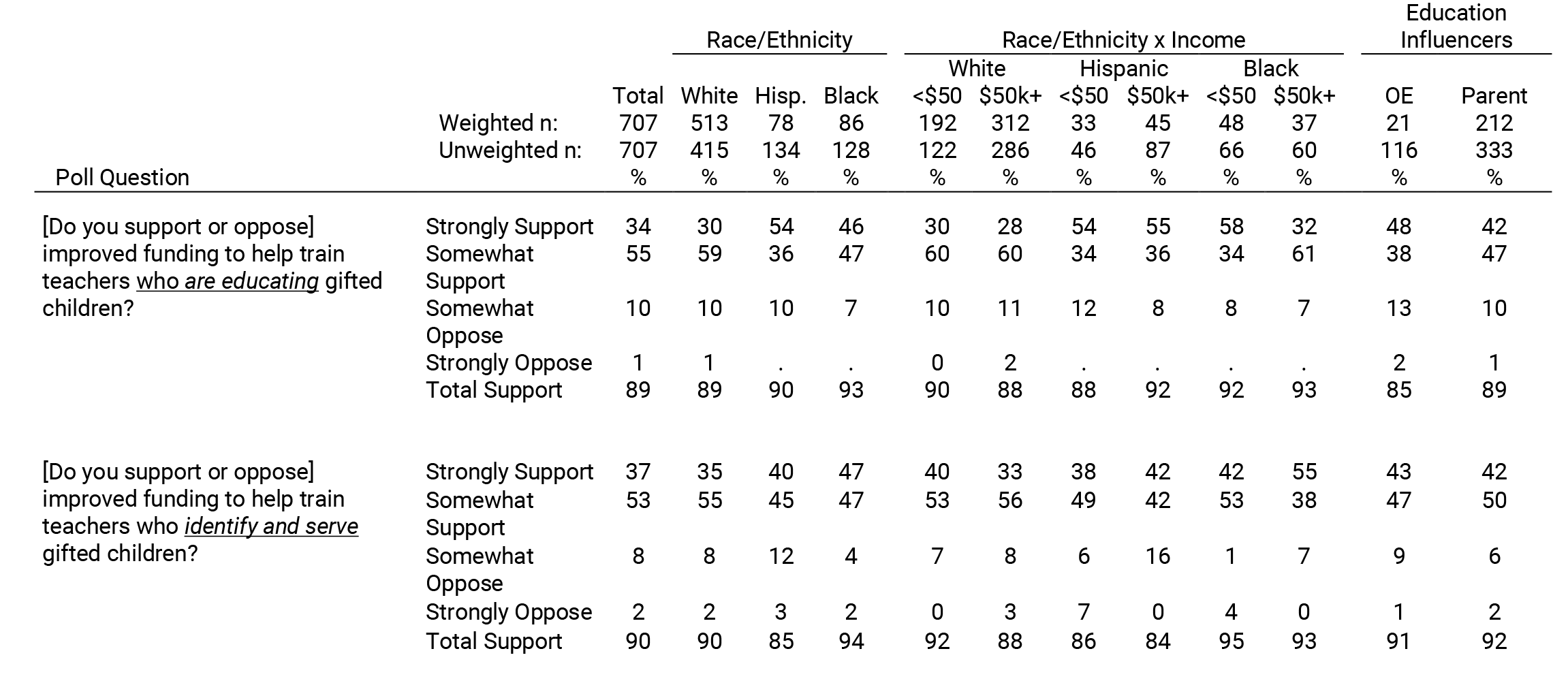

Two questions in this section of the poll tested the public’s sensitivity to words and concepts important to gifted education. Questions in this section assessed the public’s response to (1) the concept of identification, and (2) the difference between referring to programs or children when considering funding for gifted students.

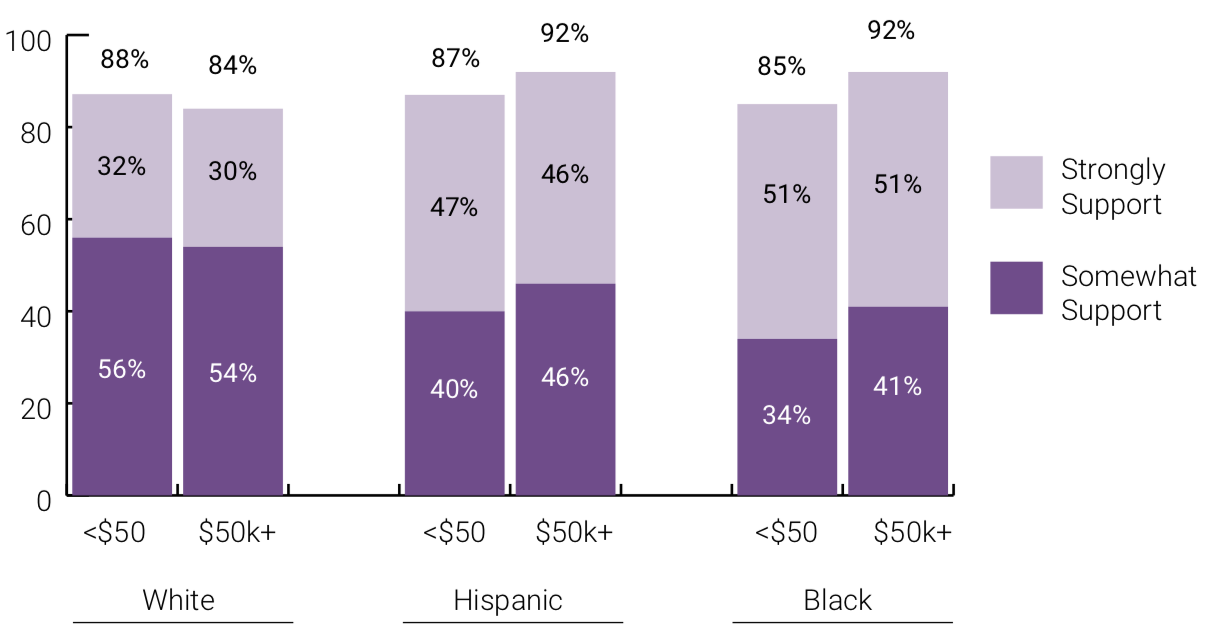

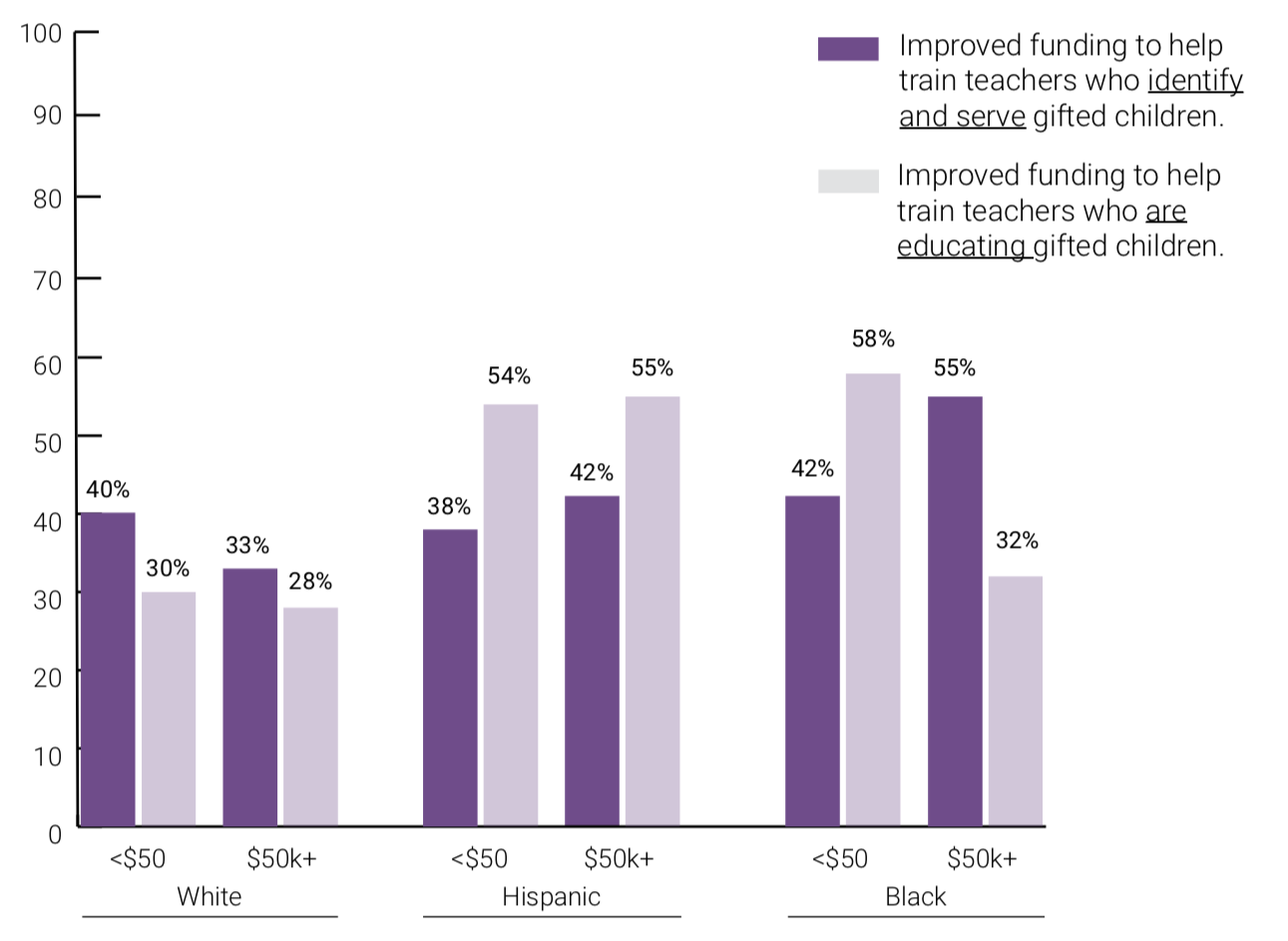

The effect of the word “identification” on public support to fund professional development in gifted education. When respondents were asked if they supported requiring specialized training for teachers who work with gifted students, the answer was a resounding “yes.” A follow-up question asked respondents to consider if they would support improved funding for the required teacher education. To assess the impact of the sometimes controversial concept of “identification” on respondents’ support for funding, the follow-up question was presented in alternate forms to randomized split-samples. The primary difference between the two variations was the inclusion of the word ‘identification’ in the second question:

Question A: Do you support improved funding to help train teachers who are educating gifted children?

Question B: Do you support improved funding to help train teachers who identify and serve gifted children?

The two questions elicited the similarly high levels of overall support, with at least 84% of each split sample in favor of improving funding to help train teachers who work with gifted children (Table 4.2). However, the level of strong support was different across subgroups (Figure 4.3).

Percentage of Respondent Support for Professional Development: Comparing Presence or Absence of the Word “Identification” in Poll Question (Q36, R8-R9)

Notes. <$50 = Income under $50,000/year, $50k+ = Income $50,000 and up, OE = Opinion Elite, Hisp = Hispanics, Total Support = the sum of Strongly Support plus Somewhat Support, “.” = to few observations to calculate. Split half samples X (are educating) and Y (identify and serve) were used for this item. See Appendix B, Table B3 for standard error of measure. Race/Ethnicity does not include respondents who selected more than one race. Race/Ethnicity x Income does not include respondents who selected “Prefer Not to Indicate.”

Education Influencers. Opinion Elites and Parents were more likely to give support when the question included identification (Total Support 91% of Opinion Elites, 92% of Parents). The difference in response to the two questions was six or seven percentage points, and always favored the question that included identification.

Racial/Ethnic Groups. When the question excluded identification, a majority of lower-income Blacks (58%), lower-income Hispanics (54%) and higher- income Hispanics (55%) indicated Strong Support. For each group, between 10% and 15% fewer respondents offered strong support when the question included identification. Conversely, lower-income White, higher-income White, and higher- income Black respondents were more likely to indicate Strong Support when the question included identification (40%, 33%, and 55%, respectively) (Figure 4.3).

Emphasizing programs or students. A similar method determined whether the public was more likely to rally around establishing gifted programs or supporting gifted students. The two questions presented to split samples asked whether funding for gifted education should match funding for students with learning disabilities; one half of respondents received the program-centered question, and the other half the student-centered question:

Program-Centered: Please indicate if you support or oppose this proposal–guaranteeing that programs for gifted students receive the same level of funding as programs for students with learning disabilities.

Student-Centered: Please indicate if you support or oppose this proposal–guaranteeing that gifted students receive the same level of funding as students with learning disabilities.

Total support was high for both student-centered and program-centered funding questions. A total of 83% supported the question with program-centered phrasing, and 81% supported the question with student-centered phrasing (Table 4.3).

Do you Support or Oppose…

Figure 4.3. Percentage of respondents reporting “Strong Support” for professional development with and without mention of identification, by race/ethnicity and income.

Education Influencers. Opinion Elites were more likely to respond with support for the program-centered question (88% support for program-centered and 78% for child-centered). Parent response was nearly identical for each question, including the same level of overall support (85% for program-centered and 86% for child-centered) and strong support (41% for program-centered and 40% for child-centered).

Racial/Ethnic Groups. Despite their generally positive responses overall, the three racial/ethnic analysis groups had different responses to the two questions. White respondents were more likely to offer support for programs (84% program-centered, 79% student- centered); this was true regardless of income level. Equal numbers of Hispanic respondents supported each version of the question (86% student-centered, 87% program-centered); however, many more higher- income Hispanic respondents offered strong support when the question was student-centered (31% program-centered, 43% student-centered). Black respondents were more likely to offer support when the question was student-centered (77% program- centered, 86% student-centered). Lower- and higher- income Black respondents differed when offering “Strong Support”; lower-income Black respondents were more likely to offer strong support for the student-centered question (41% program-centered, 58% student-centered), but higher-income Black respondents were more likely to give strong support when the question was program-centered (48% program-centered, 36% student-centered) (Table 4.3.).

Synopsis

American’s investment in gifted education rises above concern that something is wrong with respect to schooling for gifted students. The public also actively supports, and sometimes strongly supports, many commonly recommended program provisions for gifted students.

- 86% of IEA-P respondents supported required training for teachers who work with gifted children. The public wants assurance that teachers are prepared to work with all the students in their classrooms. Their concern over teacher preparation specific to gifted students also provides an indirect indicator that the public understands that educating gifted children requires knowledge and skills that go beyond preparation for the general education classroom.

- 76% of IEA-P respondents indicated concern that gifted students do not have opportunities to accelerate. Support for accelerating gifted students was reported by 86% of the IEA-P. With this level of interest among the public, and with a substantial body of evidence in its favor (Colangelo, Assouline, & Gross, 2004; Assouline, Colangelo, VanTassel-Baska, & Lupkowski-Shoplik, 2015), acceleration should be incorporated as an option for gifted students around the nation.

Percentage of Respondent Support for a Proposal to Fund Services for Gifted Education: Comparing Emphasis on Students or Programs (Q36, R4-5)

| Race/Ethnicity | Race/Ethnicity x Income | Education | |||||||||||||

| White | Hispanic | Black | Influencers | ||||||||||||

|

|

Total |

White |

Hisp |

Black |

<$50 |

$50k+ |

<$50 |

$50k+ |

<$50 |

$50k+ |

OE |

Parent |

|||

| Weighted n: | 707 | 513 | 78 | 86 | 192 | 312 | 33 | 45 | 48 | 37 | 42 | 424 | |||

|

Unweighted n: |

707 |

415 |

134 |

128 |

122 |

286 |

46 |

87 |

66 |

60 |

333 |

116 |

|||

|

Poll Question |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

|||

|

Do you support or oppose guaranteeing that programs for gifted students receive the same level of funding as programs for students with learning disabilities? |

Strongly Support |

39 |

39 |

35 |

44 |

42 |

38 |

40 |

31 |

41 |

48 |

42 |

41 |

||

|

Somewhat Support |

44 |

44 |

51 |

32 |

42 |

46 |

49 |

53 |

35 |

30 |

46 |

44 |

|||

|

Somewhat Oppose |

14 |

14 |

12 |

20 |

14 |

14 |

9 |

14 |

19 |

21 |

8 |

13 |

|||

|

Strongly Oppose |

3 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

5 |

1 |

4 |

3 |

|||

|

Total Support |

83 |

84 |

86 |

77 |

84 |

84 |

88 |

84 |

77 |

78 |

88 |

85 |

|||

|

Do you support or oppose guaranteeing that gifted students receive the same level of funding as students with learning disabilities? |

Strongly Support |

34 |

31 |

44 |

48 |

31 |

29 |

46 |

43 |

58 |

36 |

45 |

40 |

||

|

Somewhat Support |

47 |

48 |

43 |

38 |

46 |

51 |

39 |

45 |

26 |

51 |

33 |

46 |

|||

|

Somewhat Oppose |

17 |

19 |

13 |

10 |

21 |

18 |

15 |

12 |

12 |

9 |

16 |

12 |

|||

|

Strongly Oppose |

2 |

2 |

. |

4 |

2 |

2 |

. |

. |

4 |

4 |

6 |

2 |

|||

|

Total Support |

81 |

79 |

87 |

86 |

77 |

80 |

85 |

88 |

84 |

87 |

78 |

86 |

|||

Notes. <$50 = Income under $50,000/year, $50k+ = Income $50,000 and up, OE = Opinion Elite, Hisp = Hispanics, Total Support = the sum of Strongly Support plus Somewhat Support, “.” = to few observations to calculate. Split half sample X (programs for gifted students) and Y (gifted students). See Appendix B, Table B3 for standard error of measure. Race/Ethnicity does not include respondents who selected more than one race. Race/Ethnicity x Income does not include respondents who selected “Prefer Not to Indicate.”

- Prominent educators from different branches of education have ardently opposed gifted education, advocating the dismantling of gifted programs for the sake of educational equity (Margolin, 1993; Sapon-Shevin, 1994; Oakes, 1900). However, IEA-P respondents, including minority and low-income respondents, do not want gifted programs dismantled. Instead, they want better access to gifted programs and assurance that teachers of the gifted receive adequate professional development. Over 70%, and sometimes over 80%, of minority and low-income respondents supported providing program provisions for gifted students including opportunities to accelerate, to work with a mentor, or to attend a specialized online school. They do not believe that removing advanced educational opportunity is the correct way to create a level playing field.

- Public investment is highest—and action seems most likely— at the intersection of gifted education and high-profile issues in general education. This is especially true for providing teachers with professional development in gifted education and establishing gifted programs in low-income areas.

- Even though a majority of all analysis groups were supportive, subtle changes in key words and question framing had an effect on whether groups offered strong support. The effect of language on support was different for different groups. On the whole, Hispanic and lower- income Black respondents were more likely to offer strong support when the question was student-centered and focused on serving gifted students. A higher proportion of White and higher-income Black respondents offered strong support when questions about funding focused on establishing programs, and mentioned identification as well as services.

References

Margolin, L. (1993). Goodness personified: The emergence of gifted children. Social Problems, 40(4), 510-532.

Oakes, J. (1985). Keeping track: How schools structure inequality. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sapon-Shevin, M. (1994). Playing favorites: Gifted education and the disruption of community. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

PERCENT OF RESPONDENTS THAT SUPPORT THE FOLLOWING:

75% support creating a quality online school for gifted students

86% support requiring training for any teacher working with gifted students

86% support providing funding in underserved areas for gifted programs

87% support allowing identified gifted students to be accelerated

From Then to Now

The Fight for Acceleration

Professional development is the cornerstone of ensuring appropriate programs and services to gifted learners, especially regarding the use of acceleration.

—Croft & Wood, 2015

The debate over whether to accelerate gifted children spans at least nine decades. As far back as the 1930s researchers presented evidence of academic and social-emotional success among accelerated children, while noting that few schools supported the practice (Keys, 1935; Jenkins, 1943; Wilkins, 1936a; Witty & Wilkins, 1933).

Debate about acceleration continued during the dispute over ability grouping and collaborative learning, including articles in the seminal point- counterpoint series in the Journal for the Education of the Gifted (Elkind, 1988; Robinson, 1990; Sisk, 1988; Slavin, 1990). This era is also notable for a series of studies which used meta-analysis to identify trends in acceleration research (Kulik & Kulik, 1984, 1992; Rogers, 1992, 2007). The Kulik & Kulik studies gave evidence that acceleration does not advantage gifted students at the expense of other students. Instead, according to their findings, all students benefit when schools allow gifted students to accelerate as long as the curriculum is adjusted appropriately for each group of students. Rogers (2005) refined the research by investigating specific methods under the broad umbrella of acceleration. Rogers reported positive effect sizes for many recommended methods of acceleration including (1) early entrance into kindergarten and first grade, (2) grade skipping, (3) grade-based acceleration, (4) cluster grouping, (5) credit by exam, (6) full-time ability grouping, (7) subject-specific acceleration, and (8) mentorship. She also noted that evidence generally indicates positive social-emotional adjustment among students who accelerate.

Taking a Stand. A landmark event in advocacy for acceleration was the publication of A Nation Deceived (Colangelo, Assouline, & Gross, 2004) and the subsequent establishment of the Institute for Research and Policy on Acceleration at the Belin-Blank Center for Gifted Education and Talent Development. In addition to providing comprehensive syntheses of research findings documenting the efficacy of acceleration, the Belin-Blank Center and Acceleration Institute spearheaded several initiatives to help schools and districts improve the infrastructure of their acceleration practices, including the Iowa Acceleration Scale (Assouline, Colangelo, Lupkowski-Shoplik, Lipscomb, & Forstadt, 2009), Guidelines for Developing Academic Acceleration Policy (IRPA, 2009), the updated report A Nation Empowered (Assouline, Colangelo, VanTassel- Baska, & Lupkowski- Shoplik, 2015) and Developing Academic Acceleration Policies: Whole Grade, Early Entrance, & Single Subject (Lupkowski- Shoplik, Behrens, & Assouline, 2018). These experts caution that acceleration alone does not comprise an entire gifted program, and that acceleration is not the best option for every gifted child. However, they also assert, with evidence, that acceleration is an effective, cost-efficient, and relatively easy-to-implement option that is appropriate for many gifted children.

Effective

Effective

Cost-efficient

Cost-efficient

Simple

Simple

In-Demand

In-Demand

Acceleration Now. Decades of research and access to tools to ensure best practices in acceleration have shifted the needle of acceptance in public schools to some extent. Even so, state education policies guiding acceleration practices still vary widely. In a majority of states, individual Local Education Agencies (LEAs) are left to make decisions about whether students can accelerate. And the presence or absence of a policy does not always clarify whether a specific acceleration option is available: A state with no explicit acceleration policy is likely to offer Advanced Placement courses, while a state with an acceleration policy might still not allow early entrance into kindergarten.

The IEA-P adds the voice of the public to the current conversation, and the public enthusiastically supports acceleration. Over 70% of each analysis group reported concern that gifted students are not allowed to accelerate, and one-third of Black and Hispanic respondents report a great deal of concern. Moreover, over 80% of each analysis group claim they support acceleration for gifted students, with over 40% reporting strong support. The support for acceleration is unequivocal.

Then who demurs? Paradoxically, trends in the IEA-P suggest the group most hesitant about acceleration are educators. While the number of educators in the IEA-P was too small to generalize, the teachers and administrators who participated in the poll were least likely of any group to lend strong support to acceleration: 25% of this group of educators reported strong support for acceleration compared to 45% of Opinion Elites, and 41% of Black respondents. This trend is consistent with research reporting that even teachers who are supportive of gifted education are tentative about acceleration, citing concern over the social-emotional adjustment of accelerated students (Rambo & McCoach, 2012; Siegle, Wilson, & Little, 2013; Southern & Jones, 2004). Again, the answer seems to be ensuring that teachers receive accurate information about acceleration in pre-service and in- service education. At least one study shows that even modest amounts of information can change teachers’ minds in favor of acceleration (Olthouse, 2013).

The belief that acceleration is harmful perpetuates a bona fide myth. Unfortunately, this myth, held mainly by educators, seems to be a significant barrier impeding the use of a practice which is evidence- based, affordable, and supported by the American public.

Kyle’s Story:

Kyle started to read when he was two. He carried the first Harry Potter book with him to preschool and proceeded to finish the book in a week. His preschool teacher recognized Kyle’s needs and advised his parents that Kyle should skip kindergarten. At first, the school district denied the request due to policy. As a result, Kyle’s initial experience of kindergarten was fraught with boredom and frustration. He cried every morning and would try to negotiate ways to get out of going to school.

Knowing that something had to change, his parents went back to the district who then decided to take the risk and allow Kyle to accelerate to first grade. With the support of his teachers, administrators and parents, Kyle was once again motivated to learn, he was gaining confidence, making friends and maturing among his new peers. This has changed school policy, ensuring other children have similar opportunities.

References

Assouline, S. G., Colangelo, N., VanTassel-Baska, J., & Lupkowski-Shoplik, A. (2015). A nation empowered: Evidence trumps the excuses holding back America’s brightest students (Vol. I). Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa, Connie Belin & Jacqueline N. Blank International Center for Gifted Education and Talent Development.

Colangelo, N., Assouline, S. G., & Gross, M. (2004). A nation deceived: How schools hold back America’s brightest students: The Templeton report on acceleration. Iowa City, Iowa: The Connie Belin & Jacqueline N. Blank International Center for Gifted Education and Talent Development.

Elkind, D. (1988). Mental acceleration. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 11(4), 19-31.

Institute for Research and Policy on Acceleration (2009). Guidelines for developing an academic acceleration policy. Iowa City, IA: Author.

Jenkins, M. D. (1943). Case studies of Negro children of Binet IQ 160 and above. The Journal of Negro Education, 12, 159-166.

Kulik, J. A., & Kulik, C. C. (1992). Meta-analytic findings on grouping programs. Gifted Child Quarterly, 36, 73-77.

Olthouse, J. M. (2013). Improving rural teachers’ attitudes towards acceleration. Gifted Education International, 31, 154-161.

Rambo, K. E., & McCoach, D. B. (2012). Teacher attitudes toward subject-specific acceleration. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 35, 129- 152.

Robinson, A. (1990). Cooperation or exploitation? The argument against cooperative learning for talented students. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 14, 9-27.

Rogers, K. B. (1992). A best-evidence synthesis of the research on acceleration options for gifted learners. In N. Colangelo, S. G. Assouline, &

D. L. Ambroson (Eds.), Talent development: Proceedings from the 1991 Henry B. and Jocelyn Wallace national research symposium on talent development (pp. 406-409). Unionville, NY: Trillium.

Rogers, K. B. (2007). Lessons learned about educating the gifted and talented, a synthesis of the research on educational practice. Gifted Child Quarterly, 51, 382-396.

Siegle, D., Wilson, H. E., & Little, C. A. (2013). A sample of gifted and talented educators’ attitudes about academic acceleration. Journal for Advanced Academics, 24, 27-51.

Shane, H. (1960). Grouping in the elementary school. The Phi Delta Kappan, 41, 313-319. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/20342430

Sisk, D. A. (1988). The bored and disinterested gifted child: Going through school lockstep. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 11(4), 5-18.

Slavin, R. E. (1990) Point-counterpoint: Ability grouping, cooperative learning and the gifted. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 14, 3-8.

Wilkins, W. (1936a). High-school achievement of accelerated pupils. The School Review, 44, 268-273. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1080253

Wilkins, W. (1936b). The Social adjustment of accelerated pupils. The School Review, 44, 445-455. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1080718

Witty, P. A., & Jenkins, M. A. (1936). Intra-race testing and negro intelligence. The Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 1, 179-192.

Witty, P. A., and Wilkins, L. W. (1965). The status of acceleration or grade skipping as an administrative practice. In Walter B. Barbe, Ed., (1965) Psychology and education of the gifted: Selected readings. New York, NY: Appleton Century-Crofts, (pp. 390-413).