For decades, proponents of gifted education have attempted to persuade state and national leaders that gifted students need specialized programs and services. Advocates have argued that investing in America’s gifted students is in the best interest of the nation, that these children have the right to work toward their individual potential (Colangelo, Assouline, & Gross, 2004; Marland, 1972; O’Connell-Ross, 1993). Advocates have asked the public to consider the consequences to society at large when potential is unfulfilled, including the appeal, “How can we measure the sonata unwritten, the curative drug undiscovered, the absence of political insight. They are the difference between what we are and what we could be as a society” (J. Gallagher, 1975, p. 4).

These messages may be compelling to those who already believe that gifted students need services; however, there is no evidence that they are genuinely persuasive to individuals outside of the field who require convincing. It is not clear which advocacy messages are more influential than others, or whether changes in focus, phrasing, or framing might change the influence of these messages. In an attempt to fill this gap, a section of the IEA-P was devoted to two tests of commonly used gifted education advocacy messages. In one test, respondents rated the persuasive appeal of common advocacy messages when presented without counterarguments; in the second test, respondents judged the efficacy of messages that argue in favor of gifted education when presented alongside common arguments against gifted education (Chapter 6).

Stand-Alone Advocacy Messages

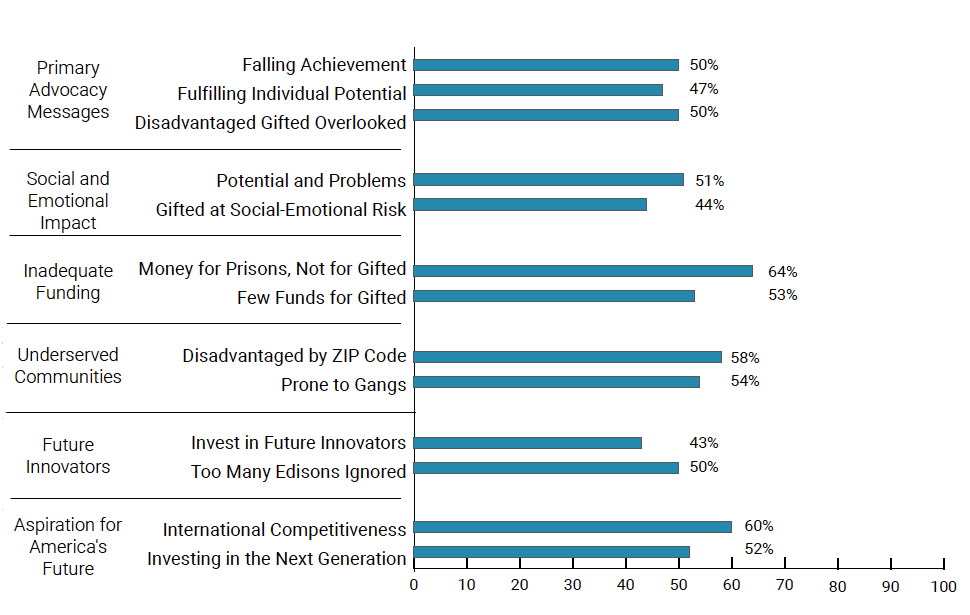

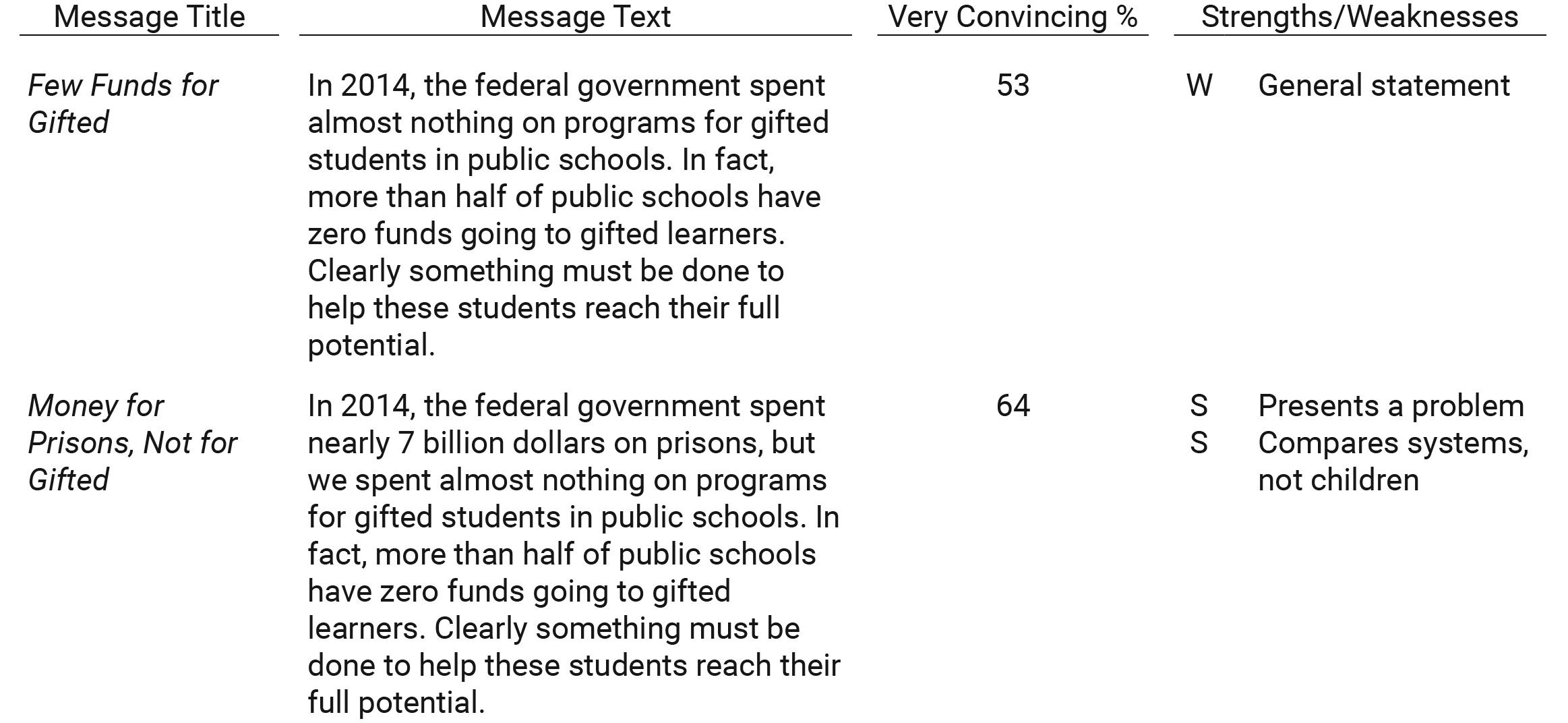

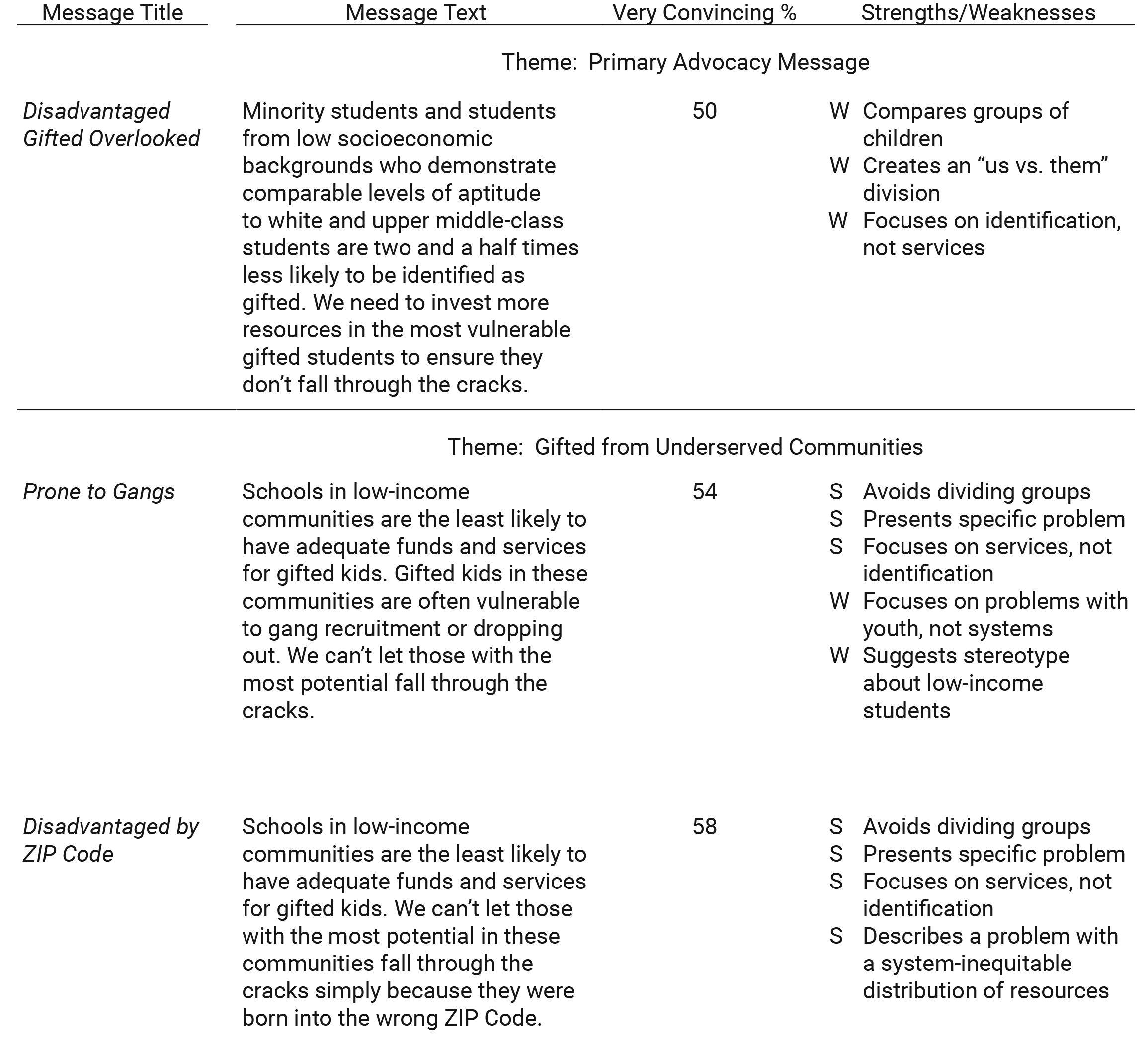

IEA-P respondents rated whether 13 advocacy messages presented convincing reasons to increase funding for gifted programs. Three of the 13 were Primary Advocacy Messages which are frequently used to persuade others of the value of gifted education (Figure 5.1). The Primary Advocacy Messages included:

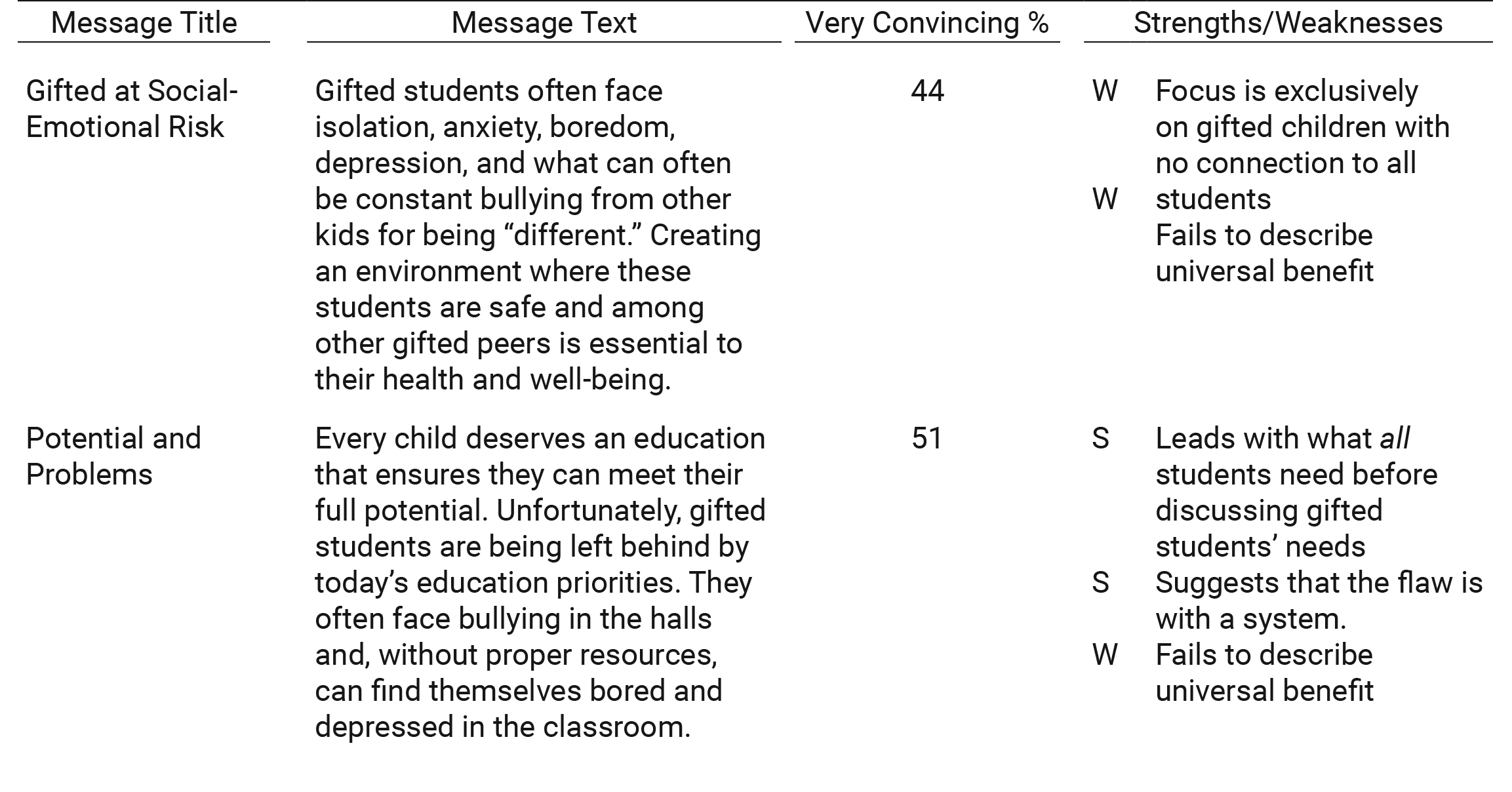

(1) Falling Achievement, which presented data about the nationwide drop in achievement levels among gifted students; (2) Disadvantaged Gifted Overlooked, which described the failure to identify low-income and minority gifted students; and (3) Right to Fulfill Potential, which claimed that gifted children have a right to fulfill their potential. The remaining ten advocacy messages were tested in pairs, with two messages for each of five themes: (1) Aspiration for America’s Future; (2) Future Innovators; (3) Gifted from Underserved Communities; (4) Few Funds for Gifted Education; and (5) Social-Emotional Impact (Figure 5.1). Using paired variations of the same message allowed for assessments of message framing as well as message content. The full text of each message is in Table 5.1.

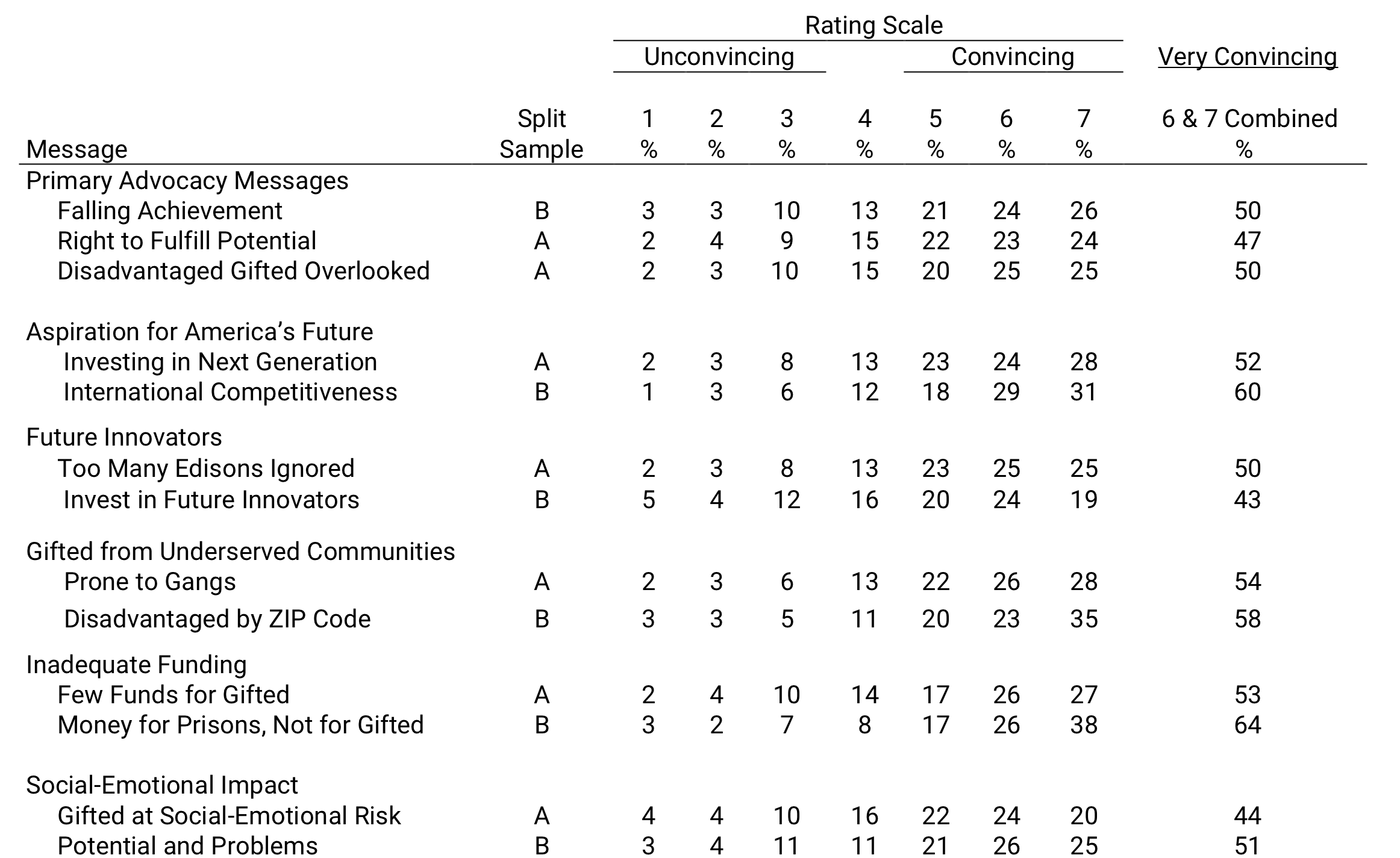

The messages were presented to randomly assigned split samples of 707 IEA-P respondents; one half of the sample responded to six messages and the other half responded to the remaining seven messages. Messages created for the same theme were assigned to different split samples. For instance, one half of the split sample responded to Aspiration for America’s Future: America as a World Leader, and the other half responded to Aspiration for America’s Future: International Competitiveness. Respondents rated each message on a seven-point scale, from 1 = Extremely Unconvincing to 7 = Extremely Convincing. Messages rated either 6 or 7 on the seven-point scale were considered “Very Convincing.” The effectiveness of a message was determined from the number of respondents who awarded a message this high rating.

Themes and messages tested in the IEA-P.

|

Theme |

Advocacy Messages |

|

Primary Advocacy Messages |

|

|

Aspiration for America’s Future |

|

|

Future Innovators |

|

|

Gifted from Underserved Communities |

|

|

Inadequate Funding |

|

|

Social-Emotional Impact |

|

Figure 5.1. Themes and messages tested in the IEA-P.

How convincing a reason is this to support increasing funding for gifted student programs…

Figure 5.2. Percentage of respondents who rated advocacy messages Very Convincing.

Effectiveness of Stand-Alone Advocacy Messages

Effective Advocacy Messages. Table 5.2 presents respondents’ ratings of how convincing they found the 13 advocacy messages, including the number who rated a message a “6” or “7,” indicating that it was Very Convincing. All 13 messages received a rating of “6” or “7” by at least 40% of a split sample; no message received Very Convincing ratings by more than 65% (Figure 5.2). None of the messages received negative ratings of “1” or “2” by more than 10% of respondents.

Highly effective messages (Very Convincing to 59-65% of IEA-P respondents) . Messages were considered highly effective if they were rated “6” or “7” on the seven point scale by a majority of respondents. These messages received high ratings by a large enough margin to suggest they would consistently receive a positive response.

Three of the 13 messages were rated Very Convincing by 59-65% of respondents (Figure 5.3). The most effective message in the poll was Few Funds for Gifted Education: Money for Prisons, Not for Gifted. This message was ranked Very Convincing by 64% of respondents and was rated a “7” by 38% of respondents. The Aspiration for America’s Future: International Competitiveness message was Very Convincing to 60% of respondents. The Gifted from Underserved Communities: Disadvantaged by ZIP Code message was Very Convincing to 59% of respondents, with 35% rating it a “7” on the seven- point scale.

Modestly effective messages (Very Convincing to 50-55% of IEA-P respondents). Modestly effective messages were rated “6” or “7” (Very Convincing) by a slight majority. Of the remaining 10 messages, seven were rated Very Convincing by 50-55% of respondents. The three highest ranked among these modestly effective messages were created for the same themes as the three highly effective messages. Gifted from Underserved Communities: Prone to Gangs focused on the possible negative consequences to low-income gifted students in the absence of gifted programs; it was rated Very Convincing by 54% of those who read it. Fifty-three percent of respondents found the Inadequate Funding: Few Funds for Gifted message Very Convincing; this message presented general information about the lack of funding for gifted education in the US. The third modestly effective message, aspiration for America’s Future: Investing in the Next Generation, focused on America as a leader in innovation and invention; it was rated as Very Convincing by 51% of respondents.

Highly Effective Messages

|

Inadequate Funding: Money for Prisons, Not for Gifted In 2014, the federal government spent nearly 7 billion dollars on prisons, but we spent almost nothing on programs for gifted students in public schools. In fact, more than half of public schools have zero funds going to gifted learners. Clearly something must be done to help these students reach their full potential.

|

|

Aspiration for America’s Future: International Competitiveness While the United States devoted almost no federal funding to developing its most promising youth, other countries like China and India invest millions of dollars in theirs. If our country wants to remain globally competitive in the coming decades, we need to ensure these gifted young Americans receive the support and resources they need to succeed.

|

|

Gifted from Underserved Communities: Disadvantaged by ZIP Code Schools in low-income communities are the least likely to have adequate funds and services for gifted kids. We can’t let those with the most potential in these communities fall through the cracks simply because they were born into the wrong ZIP code.

|

Figure 5.3. Highly effective messages.

Other modestly effective messages were ranked as Very Convincing by 50-51% of respondents. Two of the three Primary Advocacy Messages were a part of this set, including Falling Achievement, which presents NAEP data documenting decreasing achievement among gifted students, and Disadvantaged Gifted Overlooked, which focused on the need to identify low-income and minority gifted students. Social-Emotional Impact: Potential and Problems, was also in this cluster; a message which combined a call to allow gifted children to fulfill their potential with a caution about the personal price they may pay if they cannot. The lowest rated among the modestly effective messages was Future Innovators: Too Many Edisons Ignored. This message provided examples of inventors and entrepreneurs such as Beethoven, Edison, and Curie as examples of artists, inventors, and explorers who made contributions that benefitted the world at large.

Advocacy Messages Tested in the IEA-P

| Theme/Message | Message Text |

|

Primary Advocacy Messages |

|

|

Falling Achievement |

The education system currently cannot handle the needs of these [gifted] students: more than half of public school students who are scoring at an advanced level as fourth graders will be unable to sustain that level of achievement by the time they get to 12th grade. We have a responsibility to help these kids live up to their potential. |

|

Disadvantaged Gifted Overlooked |

Minority students and students from low socioeconomic backgrounds who demonstrate comparable levels of aptitude to white and upper middle-class students are two and a half times less likely to be identified as gifted. We need to invest more resources in the most vulnerable gifted students to ensure they don’t fall through the cracks. |

|

Right to Fulfill Potential |

In America, every person has the right to reach his or her full potential— that’s what the American dream is all about. We have a duty to help gifted students fulfill their dreams and reach their goals by providing the resources necessary to do so. |

|

Aspiration for America’s Future |

|

|

America as World Leader |

America has long been the world leader in entrepreneurship, discovery, and innovation. If we want to continue to lead in the future, we must invest in our nation’s most powerful resource: the great thinkers and innovators of the next generation. |

|

International Competitiveness |

While the United States devotes almost no federal funding to developing its most promising youth, other countries like China and India invest millions of dollars in theirs. If our country wants to remain globally competitive in the coming decades, we need to ensure these gifted young Americans receive the support and resources they need to succeed. |

|

Future Innovators |

|

|

Too Many Edisons Ignored |

Too many of our future Beethovens, Marie Curies, Steve Jobs, Sally Rides and Thomas Edisons are sitting in a public school classroom, bored or disengaged, without any of the programs or teachers they need. We need to invest in our future innovators—nurturing, challenging, and inspiring them to achieve greatness. |

|

Invest in Future Innovators |

The government spends the most on low-performing schools and very little on high-achieving students. We need to invest in our future innovators— nurturing, challenging, and inspiring them to achieve greatness. Gifted students are the key to America’s future and to maintaining our place in the global economy. |

| Gifted from Underserved Communities | |

|

Prone to Gangs |

Schools in low-income communities are the least likely to have adequate funds and services for gifted kids. Gifted kids in these communities are often vulnerable to gang recruitment or dropping out. We can’t let those with the most potential fall through the cracks. |

|

Disadvantaged by ZIP Code |

Schools in low-income communities are the least likely to have adequate funds and services for gifted kids. We can’t let those with the most potential in these communities fall through the cracks simply because they were born into the wrong ZIP Code. |

|

Inadequate Funding |

|

|

Few Funds for Gifted |

In 2014, the federal government spent almost nothing on programs for gifted students in public schools. In fact, more than half of public schools have zero funds going to gifted learners. Clearly something must be done to help these students reach their full potential. |

|

Money for Prisons, Not for Gifted |

In 2014, the federal government spent nearly 7 billion dollars on prisons, but we spent almost nothing on programs for gifted students in public schools. In fact, more than half of public schools have zero funds going to gifted learners. Clearly something must be done to help these students reach their full potential. |

|

Social-Emotional Impact |

|

|

Gifted at Social-Emotional Risk |

Gifted students often face isolation, anxiety, boredom, depression, and what can often be constant bullying from other kids for being “different.” Creating an environment where these students are safe and among other gifted peers is essential to their health and well-being. |

|

Potential and Problems |

Every child deserves an education that ensures they can meet their full potential. Unfortunately, gifted students are being left behind by today’s education priorities. They often face bullying in the halls and, without proper resources, can find themselves bored and depressed in the classroom. |

Ineffective messages (Very Convincing to fewer than 50% of IEA-P respondents) . Ineffective messages were rated “Very Convincing” by fewer than 50% of respondents. These messages cannot be counted on to persuade the majority of an audience, at least in their current form.

Three of the 13 messages were ineffective (Figure 5.4). One of the three Primary Advocacy Messages that fell in this group, Right to Fulfill Potential, which connects fulfilling individual potential with the American Dream, received a Very Convincing rating from 47% of the respondent group. Social- Emotional Impact: Gifted at Social-Emotional Risk, focusing on personal negative consequences when a gifted child’s potential is not fulfilled, was rated Very Convincing by 44% of respondents. The Future Innovators: Invest in Future Innovators message, which contained a generic appeal to invest in tomorrow’s innovators, was rated Very Convincing by 43% of respondents.

Percentage of Responses to: “How Convincing a Reason is this to Support Increasing Funding for Gifted Student Programs….” (Q49-61).

Notes. Split Sample A and B n = 707 each, for standard error of measure see Appendix B, Table B3.

Variation in message effectiveness by analysis subgroup. Table 5.3 presents a breakdown of respondent reaction to the advocacy messages by analysis subgroups. Only one of the three highly effective messages, Inadequate Funding: Money for Prisons, Not for Gifted, met the criteria for an effective message with the aggregate sample and also with each analysis subgroup.

Education Influencers. Two messages were highly effective with both Opinion Elites and Parents. Over 60% of each group found the messages Inadequate Funding: Money for Prisons, Not for Gifted and Aspiration for America’s Future: International Competitiveness Very Convincing. The only place where Parents and Opinion Elites differed by a substantial margin was for Disadvantaged Gifted Overlooked, which was effective with Opinion Elites (65% Very Convincing), but ineffective with Parents (43% Very Convincing). Opinion Elites were the only group who favored Prone to Gangs over Disadvantaged by ZIP Code under the Gifted from Underserved Communities theme. This was the only time ratings by Opinion Elites did not mirror the preferences of other analysis groups.

Ineffective Messages

|

Primary Advocacy Message: Fulfilling Potential

|

|

Social-Emotional Impact: Gifted at Social- Emotional Risk

|

|

Future Innovators: Invest in Future Innovators

|

Figure 5.4. Ineffective messages.

Only 38% of Opinion Elites and 39% of Parents rated Future Innovators: Invest in Future Innovators Very Convincing, making it an ineffective message for both groups. This was particularly notable for Opinion Elites, as over 50% of that group rated every other message Very Convincing.

Racial/Ethnic Groups. Inadequate Funding: Money for Prisons, Not for Gifted, the only message that was highly effective with the aggregate group and with all subgroups, was Very Convincing to 65% of White respondents and 62% of Black and Hispanic respondents. The alternate form of the message, Inadequate Funding: Few Funds for Gifted omitted mention of prisons and was highly effective only with Black respondents (61% Very Convincing).

The only other message which was Very Convincing across all three racial/ethnic groups was Aspiration for America’s Future: International Competitiveness. This message was rated as Very Convincing by 60% of the overall sample, including 60% of White, 64% Hispanic, and 56% Black respondents.

The Primary Advocacy Message: Disadvantaged Gifted Overlooked evoked very different responses across racial/ethnic groups, just as it did between Opinion Elites and Parents. The message was highly effective with Black respondents (64% Very Convincing), modestly effective with Hispanic respondents (54% Very Convincing), and it was ineffective with White respondents (44% Very Convincing).

The Future Innovators: Invest in Future Innovators message, which was the lowest rated message among all groups, was substantially less effective with Black respondents as compared to White or Hispanic respondents. Only 35% of Black respondents rated this message Very Convincing, the single lowest rating by any group for any message.

Effectiveness of advocacy themes. The three most effective themes in the poll were: (1) Aspiration for America’s Future, (2) Gifted from Underserved Communities, and (3) Inadequate Funding. The six messages under these three themes received the highest ratings from IEA-P respondents, suggesting respondents found the themes compelling above and beyond their specific messages.

The remaining two themes, Social-Emotional Impact and Future Innovators, were less successful with poll respondents. One unifying factor that could explain the low ratings is that the themes and their respective messages emphasized the needs of gifted students without a direct mention of societal benefits.

Percentage of Respondents who Found Advocacy Messages “Very Convincing,” Education Influencers and Racial/Ethnic Group

|

Message |

Split Sample |

Race/Ethnicity White Hispanic Black % % % |

Education Influencers % % |

|||

|

Primary Advocacy Messages |

|

|

|

|||

|

Falling Achievement |

B |

52 |

42 | 45 |

52 |

48 |

|

Right to Fulfill Potential |

A |

48 |

53 | 52 |

59 |

55 |

|

Disadvantaged Gifted Overlooked |

A |

44 |

54 | 64 |

65 |

43 |

|

Aspiration for America’s Future |

|

|

|

|||

|

America as World Leader |

A |

50 |

54 | 54 |

58 |

46 |

|

International Competitiveness |

B |

60 |

64 | 56 |

64 |

59 |

|

Future Innovators |

||||||

|

Too Many Edisons Ignored |

A |

49 |

54 |

51 |

55 |

48 |

|

Invest in Future Innovators |

B |

43 |

44 |

35 |

38 |

39 |

|

Gifted from Underserved Communities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Prone to Gangs |

A |

51 |

59 |

61 |

64 |

54 |

|

Disadvantaged by ZIP Code |

B |

57 |

60 |

64 |

56 |

58 |

|

Inadequate Funding |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Few Funds for Gifted |

A |

52 |

53 |

61 |

56 |

53 |

|

Money for Prisons, Not for Gifted |

B |

65 |

62 |

62 |

61 |

63 |

|

Social-Emotional Impact |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gifted at Social-Emotional Risk |

A |

42 |

50 |

46 |

51 |

48 |

|

Potential and Problems |

B |

51 |

55 |

45 |

54 |

50 |

Note. Weighted n = 707 for Split Samples A and B. For subgroup sample size and measurement errors see Appendix B, Table B3. Race/Ethnicity does not include respondents who selected more than one race. Race/Ethnicity x Income does not include respondents who selected “Prefer Not to Indicate.”

Matching message and audience. Considerable variation was observed in the effectiveness of messages across analysis subgroups of the IEA-P. Messages rated as Very Convincing by over 60% of analysis subgroups are presented in Figure 4.10.

Opinion Elites and Blacks were most likely to respond positively to a broad range of messages. Notably, three of the four messages that were highly effective with Opinion Elites were also highly effective with Black respondents: Gifted from Underserved Communities: Prone to Gangs, Inadequate Funding: Money for Prisons, Not for Gifted, and Disadvantaged Gifted Overlooked. On the other hand, the Falling Achievement message was only modestly effective with Opinion Elites and was ineffective with Black respondents. Messages that either told a story or were success-oriented were better received.

Even though Hispanic and Black respondents were more likely to find advocacy messages convincing, a message would not achieve a comfortable majority of over 60% of the entire sample unless White respondents were also persuaded. A perfect example was the message Disadvantaged Gifted Overlooked, where 64% of Blacks but only 44% of Whites rated the message Very Convincing. In this case, the message was effective for Black respondents but ineffective for White respondents, and because of the difference in sample size, the message was only modestly effective overall.

Ineffective, modestly effective, and highly effective messages.

| Ineffective Messages | Modestly Effective Messages | Highly Effective |

|

Primary Advocacy Message: Right to Fulfill Potential Social-Emotional Impact: Gifted at Social-Emotional Risk Future Innovators: Invest in Future Innovators |

Inadequate Funding: Few Funds for Gifted Aspiration for America’s Future: Investing in the Next Generation Gifted from Underserved Communities: Prone to Gangs Social-Emotional Impact: Potential and Problems Future Innovators: Too Many Edisons Ignored Primary Advocacy Message: Disadvantaged Gifted Overlooked Primary Advocacy Message: Falling Achievement |

Inadequate Funding: Money for Prisons, Not for Gifted Aspiration for America’s Future: International Competitiveness Gifted from Underserved Communities: Disadvantaged by ZIP Code |

Figure 5.5. Ineffective, modestly effective, and highly effective messages.

Parents are also crucial allies and advocates for educational issues, so it is notable that the only messages that met the threshold for a highly effective message with Parents in the IEA-P were Inadequate Funding: Money for Prisons, Not for Gifted (63%), Aspiration for America’s Future: International Competitiveness (59%) and Gifted from Underserved Communities: Disadvantaged by ZIP Code (58%). In general, the advocacy messages in the IEA-P were less effective with White respondents and Parents than they were for other subgroups.

Comparing Paired Messages for the Same Theme

Messages that included specific examples or comparisons were more effective than general messages.

The power of language is revealed in respondents’ differing reactions to the two advocacy messages for each theme. Although the basics of advocacy messaging are to answer the questions “What is wrong?”, “Why does it matter?”, and “What should be done?” numerous advocacy groups have added additional guidelines to help refine advocacy messages and increase their effectiveness (Figure 5.6). Comparisons of different messages representing the same theme in the IEA-P provide clear examples of the benefits of attending to these recommendations.

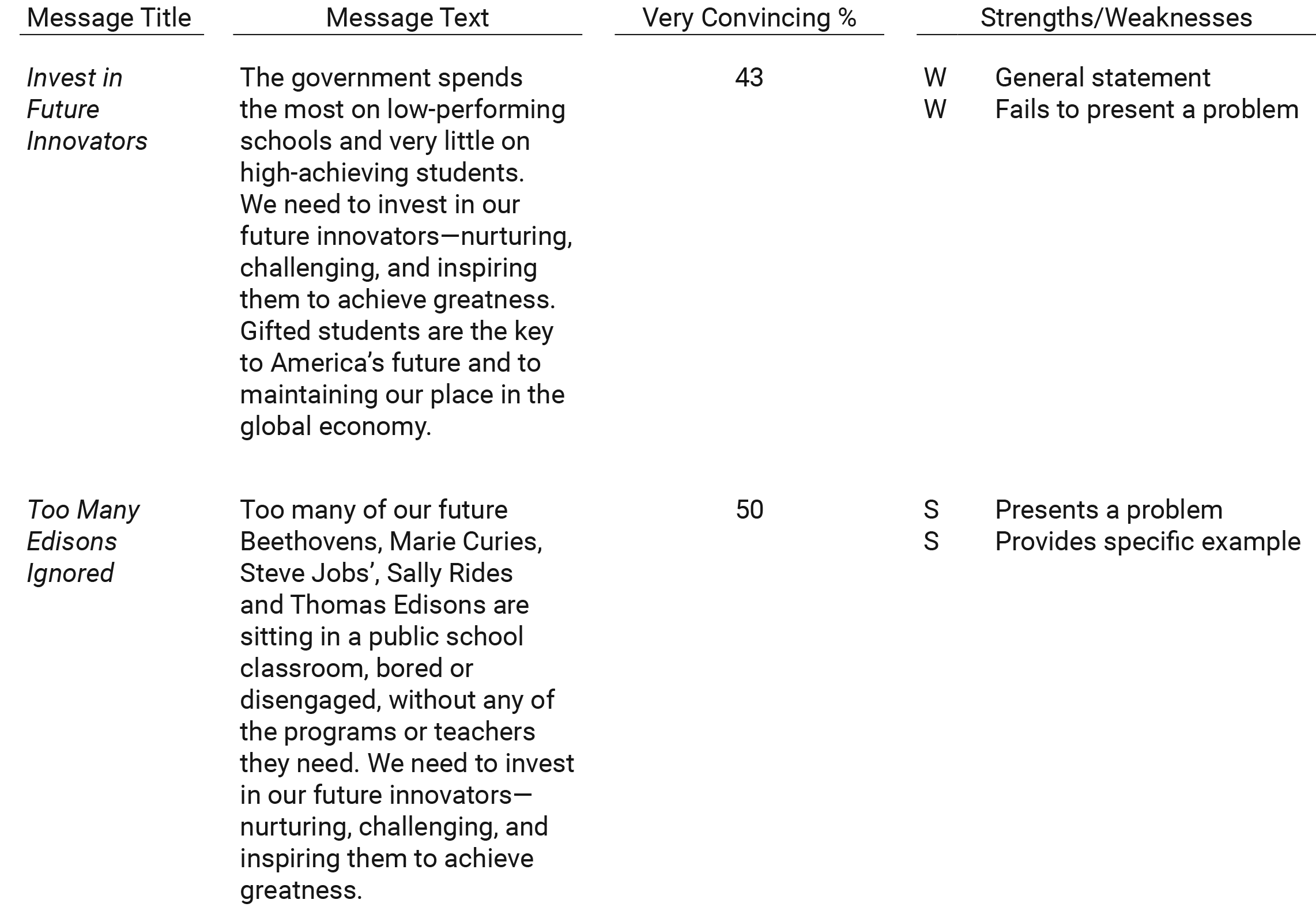

State a problem. Messages that stated a clear problem were more effective than messages with general aspirational statements. The Invest in Future Innovators message describes the status quo and presents an uplifting goal but fails to state a problem to grab the public’s attention (Table 5.5).

Dos and Don’ts of Writing Advocacy Messages

| Do | Don’t | |

|

Do lead with essential human values (e.g. fairness, justice). |

Don’t lead with the problem. |

|

|

Do define a problem and suggest solutions. |

Don’t place blame on people or groups of people instead, focus on flaws in the system. |

|

|

Do invoke sense of optimism and capacity to solve the problem. |

Don’t insert wedges between important constituent groups. |

|

|

Do provide specific examples that explain the need for change. |

Don’t put race, income, or cultural differences early in the message. |

|

|

Do explain how values are undone by the problem. |

Don’t present a problem without suggesting a path to a solution or an actual solution. |

|

|

Do appeal to a united, inclusive community. |

Don’t emphasize the historical legacy of disadvantage. |

|

|

Do evoke “enlightened self-interest”; include reminders that failures in social structures ultimately hurt everyone. |

Don’t present data in isolation. |

|

|

Do emphasize shared societal fate, opportunity, or benefit. |

||

|

Do identify your advocacy group as a part of a larger community. |

Note. Compiled from Center for Community Change, 2017; Dorfman, Wallack, & Woodruff, 2005; Kennedy, Fisher, & Bailey, 2010

The message also leads with a comparison that could create conflicted feelings among people who also support improvements for low-income schools. Even though Invest in Future Innovators presented a forward-thinking vision, this was the least effective message. The Too Many Edisons Ignored message presents a problem—future innovators are neglected in school. While this message was not as effective as others in the poll, it had a much better reception than the parallel Invest in Future Innovators message, and by a large margin among Blacks, Parents, and Opinion Elites.

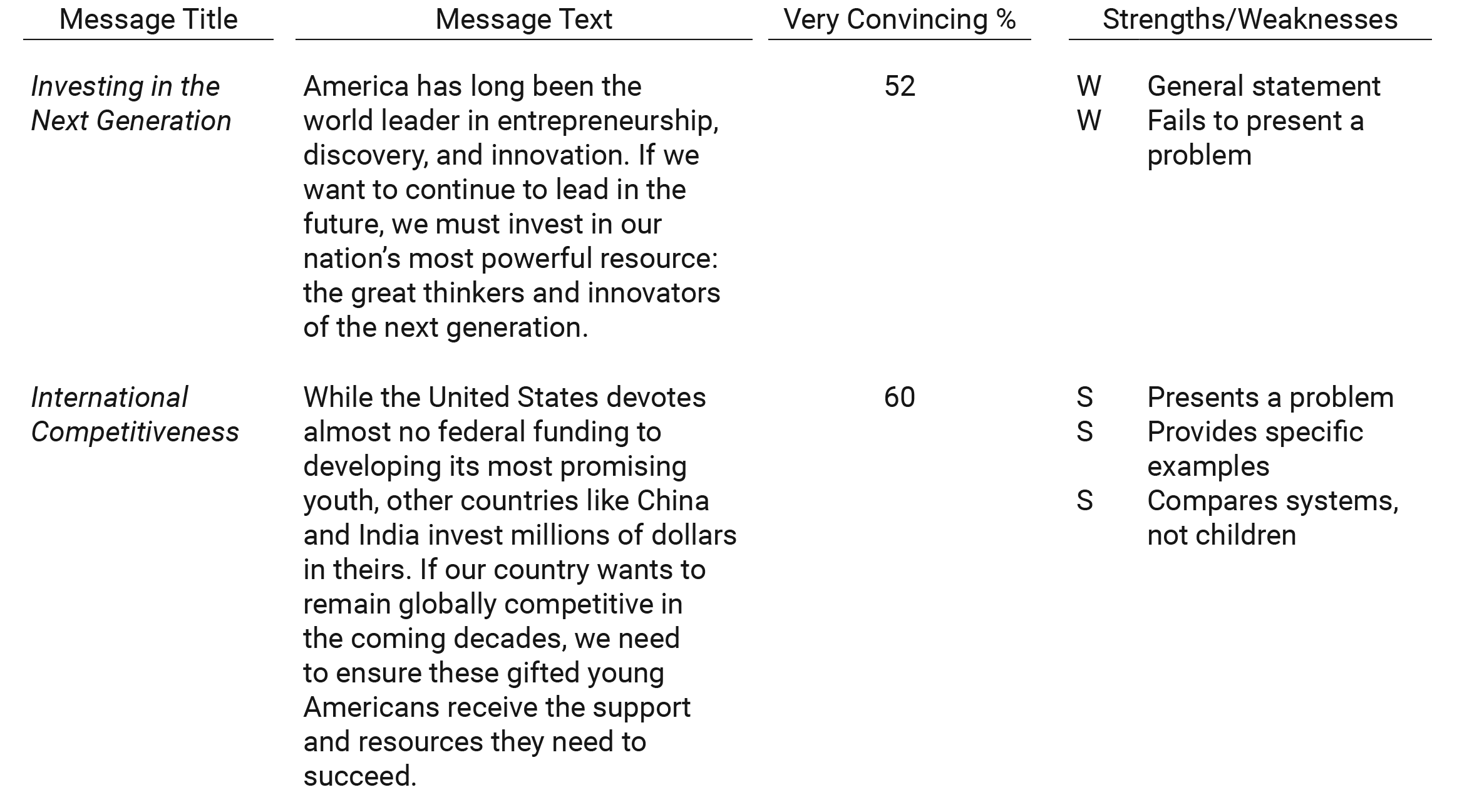

Provide specific examples that explain the need to change. Messages that included specific examples or comparisons were more effective than general messages. For example, Aspiration for America’s Future: Investing in the Next Generation only provided a general message describing a desire for America to preserve its dominance in innovation, with nothing specific used as a reference point and little sense of urgency (Table 5.6). This message was modestly effective, rated as Very Convincing by 51% of the sample. However, 60% of respondents found the alternate message, Aspiration for America’s Future: International Competitiveness, which compared America’s investment in gifted children with investments made by China and India, Very Convincing. Adding specific competitors in the international race for intellectual leadership was much more convincing than the generalities in the alternate message.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Messages for the Theme: Future Innovators

Note. W = Weakness, S = Strength.

Respondent reactions to the messages for the theme Inadequate Funding provide another clear example of the benefits of including a specific example in an advocacy message (Table 5.7). The two messages tested for this theme were identical except for nine additional words in Money for Prisons, Not for Gifted: “…spent nearly 7 billion dollars on prisons, but we….”. Even though the only difference in the two messages was a nine-word passage 64% of respondents found the Money for Prisons, Not for Gifted version Very Convincing, compared to 53% for Few Funds for Gifted. However, examples that compare groups of people tend to divide audiences and do more harm than good; these should be avoided.

Appeal to a united, inclusive community. Messages that addressed a unified group were more effective than messages that created an “us vs. them” divide. Comparing groups of people inherently divides constituents and automatically diminishes the power of an advocacy message to persuade a majority of the public. The impact of dividing the public was evidenced in the responses to three advocacy messages related to underserved gifted students (Table 5.7). Although a majority of respondents were in favor of increasing the number of programs for gifted students in low-income areas (see Chapter 3), they did not find the Disadvantaged Gifted Overlooked message, which directly compared lower- and higher- income students, very convincing. More specifically, Disadvantaged Gifted Overlooked was appealing to Black and Hispanic respondents and Opinion Elites, but not to a majority of White respondents, only 44% of whom gave the message a Very Convincing rating. The overall result was a modestly effective message.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Messages for the Theme: Aspirations for America’s Future.

Table 5.6Note. W = Weakness, S = Strength.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Messages for the Theme: Inadequate Funding

Note. W = Weakness, S = Strength

Strengths and Weaknesses for Advocacy Messages: Overlooked Disadvantaged Gifted, Prone to Gangs, and Disadvantaged by ZIP Code

Note. W = Weakness, S = Strength

Messages that described collective societal benefits of educating gifted students were more successful than messages that focus on benefits to the gifted child.

The two messages tested for the theme Gifted from Underserved Communities, which address the same general topic as Disadvantaged Gifted Overlooked, were better received. Like Disadvantaged Gifted Overlooked, both messages for Gifted from Underserved Communities present accurate information about disparities in funding for gifted education in low-income neighborhoods but the messages focus exclusively on low-income communities instead of drawing distinctions between lower- and higher-income groups. Hispanic, Black, and Opinion Elite respondents preferred the two Gifted from Underserved Communities messages over Disadvantaged Gifted Overlooked, and the messages were also Very Convincing to over 50% of the remaining poll respondents. Given the poll respondents’ differing responses to the concept of identification (see Chapter 4), it is worth noting that the less effective Disadvantaged Gifted Overlooked message also mentioned identification, while both Gifted from Underserved Communities messages both emphasize providing services.

Emphasize shared societal fate, opportunity, or benefit. Messages that described collective benefits of educating gifted students were more successful than messages that focus on benefits to the gifted child. Economic security, preservation of American values, and proactive investment in potential were all compelling. The two messages describing gifted students’ frustration and boredom were relatively ineffective (Table 5.9). Even messages about innovators, who arguably benefit the whole of society, failed to be effective if the message did not make reference to a social benefit. The Future Innovators: Invest in Future Innovators message was rated as Very Convincing by only 43% of the sample and was the single lowest rated message for three subgroups (Blacks 35%, Opinion Elites 38%, and Parents 39%). Its alternate form, which included several specific examples of innovators whose names call to mind their transformative contributions, was more effective, rated as Very Convincing by 51% of the overall sample.

Strengths and Weaknesses for the Theme: Gifted at Social-Emotional Risk

Note. W = Weakness, S = Strength

Strengths and Weaknesses of Messages for the Theme: Gifted from Underserved Communities.

Note. W = Weakness, S = Strength

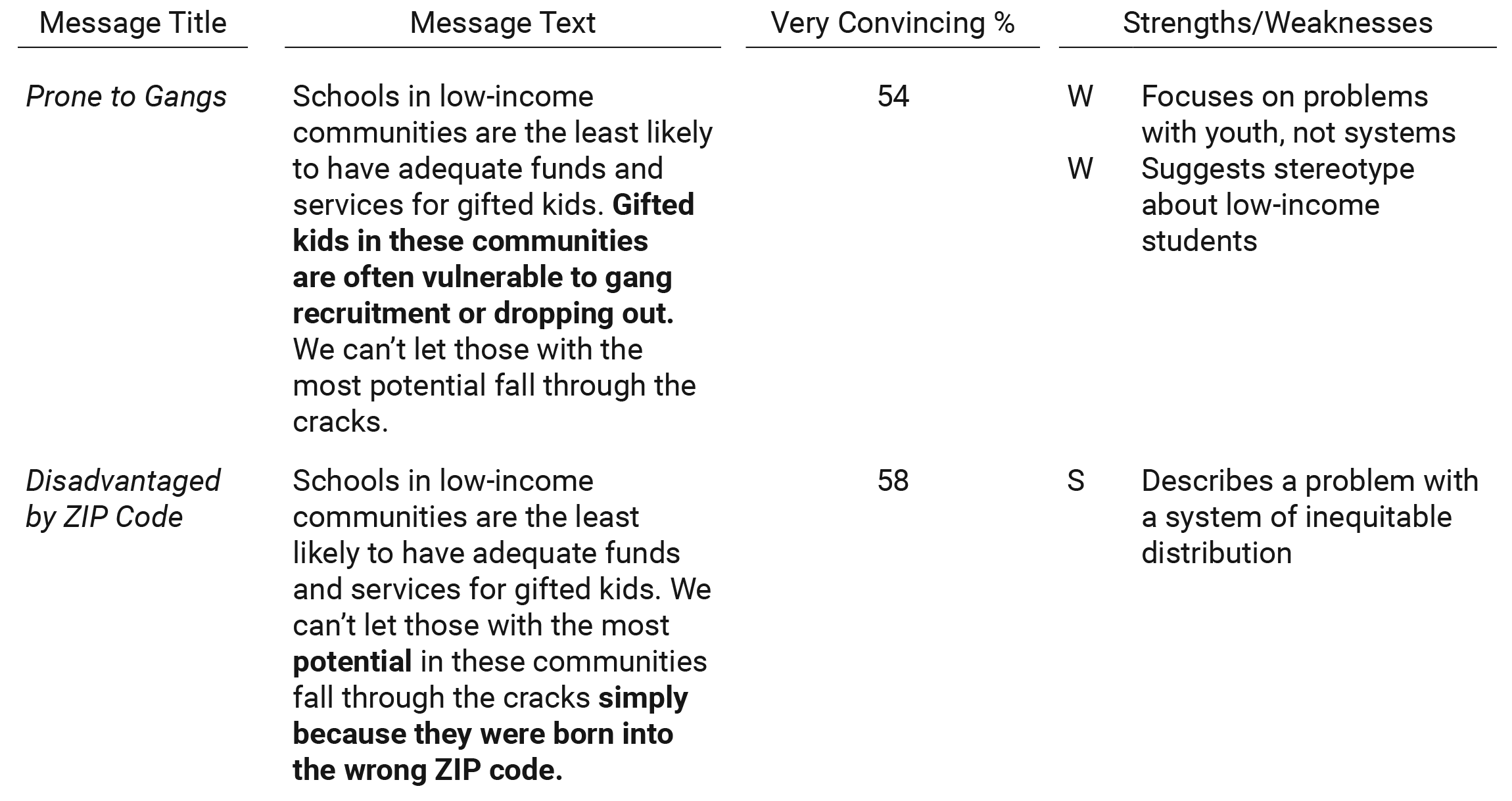

Focus on flaws in systems (don’t blame people). Messages that pointed out how broken social, economic, and/or political systems create problems are more successful than messages that suggest that people are the problem. Although messages for Gifted from Underserved Communities shared common strengths in maintaining a united constituent group and presenting a specific problem (Table 5.10), and although they shared nearly identical phrasing, they also have a crucial difference. One message suggested that low-income students are at risk for negative behaviors, and the other described economic disparities in birthplace– being born in the wrong ZIP code. Even though the two messages differed by only a few words, the Disadvantaged by ZIP Code message was more effective than the Prone to Gangs message with all groups except Opinion Elites. One reason for the difference could be the tacit suggestion in the Prone to Gangs message that low-income youth are prone to negative behaviors and lack the resilience to resist. The ZIP code message focuses on the “accident of birth” that places students in different neighborhoods, directing attention to inequities in social and economic systems.

Don’t present data in isolation. Reports presenting data trends are an asset to advocacy; they document similarities and differences between groups along specific metrics, serve as deep background for policy formation, and ensure that policy is directed to necessary targets (Finn & Wright, 2015; Plucker & Peters, 2016; Xiang, Dahlin, Cronin, Theaker, & Durant, 2011). However, advocacy messages that only present data rarely persuade, as evidenced by the modest response to the Falling Achievement message. While the public needs to have accurate, evidence-based information, they engage more deeply with messages with context that breathes life into the data.

Synopsis

The power of any advocacy message shifts with the winds of the times. In the late 1950s, the launch of Sputnik gave the International Competitiveness message extraordinary urgency that it lacks today. The results of this section of the poll require interpretation in current social context, at a time when concern is high for many areas of public education.

- All of the messages presented independently were Very Convincing to at least 40% of poll respondents. No message was Very Convincing to more than 65% of poll respondents.

- The six highest rated messages belonged to three themes: (1) Inadequate Funding, (2) Aspiration for America’s Future, and (3) Gifted from Underserved Communities.

- Three of the 13 messages were highly effective, rated as Very Convincing by 58-65% of poll respondents: (1) Inadequate Funding: Money for Prisons, Not for Gifted, (2) Gifted from Underserved Communities: Disadvantaged by ZIP Code, and (3) Aspiration for America’s Future: International Competitiveness. Only one message, Inadequate Funding: Money for Prisons, Not for Gifted, was highly effective with the overall respondent group and each of the analysis subgroups.

- Highly effective messages engaged respondents in “enlightened self-interest” by suggesting educating gifted students could improve the larger social landscape; these messages were more effective than generic messages or messages that focus on individuals fulfilling their potential.

- None of the three Primary Advocacy Messages were highly effective. While the arguments presented in Falling Achievement, Disadvantaged Gifted Overlooked, or Right to Fulfill Potential may resonate with parents and professionals who work with gifted children, they did not seem immediately persuasive to a majority of the public.

- Effective messages about disadvantaged gifted students focus on remedying social inequities, not on stereotypical dire consequences if services are not provided.

- When asked to describe gifted or high-ability students, IEA-P respondents kept a narrow focus on core attributes associated with advanced cognitive ability or achievement orientation. When responding to advocacy messages, they also preferred messages which focused on students’ abilities instead of on gifted students’ social-emotional needs.

References

Colangelo, N., Assouline, S., & Gross, M. (2004). A nation deceived: How schools hold back America’s brightest students. Iowa City, IA: The Connie Belin & Jacqueline N. Blank International Center for Gifted Education and Talent Development.

Finn, C. E., & Wright, B. L. (2015). Failing our brightest kids: The global challenge of educating high-ability students. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Gallagher, J. J. (1974). Talent delayed—talent denied: A conference report. Reston, VA: The Foundation for Exceptional Children.

Marland, S. P., Jr. (1972). Education of the gifted and talented. Report to the Congress of the United States by the U.S. Commissioner of Education and background papers submitted to the U.S. Office of Education, 2 vols. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. (Government Documents Y4.L 11/2: G36)

O’Connell-Ross, P. (1993). National excellence: A case for developing America’s talent. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Government Printing Office.

Plucker, J. A., & Peters, S. J. (2016). Excellence gaps in education: Expanding opportunities for talented youth. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Xiang, Y., Dahlin, M., Cronin, J., Teaker, R., & Durant, S. (2011). Do high flyers maintain their altitude? Performance trends of top students. Washington, DC: Thomas B. Fordham Institute. Retrieved from http://edexcellence.net/publications/high-flyers.html.

Public Perception and Professional Practice:

The Long Road to Equity in Gifted Education

…neither have we made more than a few sporadic attempts to discover gifted Negro children, nor have we attempted to see that those who have been discovered are given the advantages commensurate with their abilities.

—Editorial Comment, Journal of Negro Education, 1935 1 [1]

Despite the United States’ image of being the land of opportunity, for many children living in poverty, access to gifted education opportunities is often limited.

—Goings & Ford, 2018

IEA-P respondents were unequivocal in their desire for public schools to provide specialized programming for gifted low-income and minority students. This remains one of the most entrenched problems in gifted education.

Investigation into the needs of gifted disadvantaged students began in the 1930s when a handful of researchers began documenting the presence of advanced ability in Black children (Jenkins, 1943, 1948; Robinson & Meenes, 1947; Theman & Witty, 1943; Witty & Jenkins, 1934). It took another 15 years and school desegregation for the topic to take hold in mainstream gifted education (Cowles & Daniel, 1968; Frierson, 1965; Gowan, 1968; Tisdall, 1968), and slightly longer for the field to recognize that, although they are interrelated, racial bias and poverty suppress ability in different ways (Passow, 1972). Efforts on behalf of minority and disadvantaged gifted students expanded following the Marland Report (1972). Contributions from this time include a compendium of recommended practices for different underprivileged groups from the National/ State Leadership Training Institute (Miley, 1975), the Baldwin Identification Matrix (Baldwin, 1977), and policy recommendations from the interdisciplinary conference Talent Delayed, Talent Denied (J. Gallagher, 1974).

Today, efforts are no longer “sporadic.” The past 30 years in gifted education are defined by concerted attempts to improve the status of gifted low-income and minority students. This effort is directed in large part by the Jacob K. Javits Gifted and Talented Act, which requires funded projects to address the needs of students traditionally underrepresented in gifted programs. The Javits program has spurred innovation in identification matrices (Frasier, 1991; Maker, 2001; Shaklee, 1992) and curriculum-based in situ identification methods (Coleman & Shah-Coltrane, 2010; Gallagher & Gallagher, 2013) as well as curriculum designed to engage gifted disadvantaged learners (S. Gallagher, 2000; Gavin et al., 2007; Robinson, Adelson, Kidd, & Cunningham, 2018; VanTassel-Baska, 2018). National reports produced during this period provide summaries of evidence- based strategies and program models to identify and engage gifted students from all corners of society (Olszewski-Kubilius & Clarenbach, 2012; VanTassel- Baska & Stambaugh, 2007).

The Javits projects provide pockets of hope, yet the problem persists on a scale far more extensive than short-term, small-scale projects can address. Evidence suggests that, nationwide, high achievers who attend low-income schools perform one grade- level lower than their counterparts in higher-income schools (Wyner, Bridgeland, & Diulio, 2007). Poverty is a chief culprit in achievement disparities. Even in an educational climate where many gifted children are underachieving relative to their ability (S. Gallagher, 2007; Xiang, Dahlin, Cronin, Theaker, & Durant, 2011), underachievement in low-income populations is far more profound. For instance, there is a marked income-based disparity in the number of students who score at the Advanced level of the National Assessment of Educational Progress (Lamprey, Dion, & Donahue, 2009; Plucker & Peters, 2018). However, income alone cannot account for the opportunity gap: several studies demonstrate that minority students are referred for gifted services less often than White students, even when accounting for prior achievement and economic status (Grissom & Redding, 2016; McBee, 2006; Siegle & Powell, 2004). Inequitable access to gifted education services is systemic as well as individual; within a district, gifted programs and advanced courses are more often located in higher-income schools (Hamilton et al., 2018; Klugman, 2013). Access to gifted education is, in fact, often determined by ZIP code.

While professionals in gifted education continue to make inroads on this problem, progress is hampered by the fact that gifted education is entangled in public education’s larger struggle to provide an appropriate education for all minority and low-income students. In many school districts, leaders for gifted education programs lack the authority and the resources needed to create equitable programs. Long-term solutions are unlikely unless entire school systems engage with the problem; otherwise the wisdom gained from decades of Javits projects will help only a fortunate few, not a generation. Accordingly, some of the most important advocacy efforts on behalf of gifted students are those directed to colleagues in different branches of education, including:

Early childhood educators. Poverty impacts achievement as early as first grade. District-wide identification approaches will be most effective if implemented before income-based achievement gaps have a chance to grow.

Early childhood educators. Poverty impacts achievement as early as first grade. District-wide identification approaches will be most effective if implemented before income-based achievement gaps have a chance to grow.

Title I personnel. Students attending low-income schools are less likely to be identified as gifted, either because of low expectations or because of the absence of gifted programs in low-income schools. Title 1 personnel are crucial allies in bringing gifted identification programs, curriculum, and professional development to low-income schools.

Title I personnel. Students attending low-income schools are less likely to be identified as gifted, either because of low expectations or because of the absence of gifted programs in low-income schools. Title 1 personnel are crucial allies in bringing gifted identification programs, curriculum, and professional development to low-income schools.

Teacher preparation and professional development programs. Teacher referral is a gateway to many gifted programs; currently, those referrals are made by teachers with little or no background in gifted education. Providing information to general education teachers about gifted child characteristics, including non-traditional expression of those characteristics, is crucial to achieving equity in gifted programs. Special efforts to recruit Black and Hispanic educators into the gifted education community is also vital to creating program equity.

Teacher preparation and professional development programs. Teacher referral is a gateway to many gifted programs; currently, those referrals are made by teachers with little or no background in gifted education. Providing information to general education teachers about gifted child characteristics, including non-traditional expression of those characteristics, is crucial to achieving equity in gifted programs. Special efforts to recruit Black and Hispanic educators into the gifted education community is also vital to creating program equity.

Curriculum coordinators. Many effective interventions for low-income gifted students involve integrating engaging, inquiry-based curriculum in the regular classroom in low-income schools so that teachers can see which students respond to challenge with higher level thinking. Curriculum coordinators must commit to adopting these curricula, providing an opportunity to raise the achievement ceiling as well as its floor.

Curriculum coordinators. Many effective interventions for low-income gifted students involve integrating engaging, inquiry-based curriculum in the regular classroom in low-income schools so that teachers can see which students respond to challenge with higher level thinking. Curriculum coordinators must commit to adopting these curricula, providing an opportunity to raise the achievement ceiling as well as its floor.

District leadership. Motivating and coordinating the intra-disciplinary efforts described above requires the leadership of district administration. Creating equity in gifted programs also requires investment of time and resources. District leaders demonstrate commitment to a cause through budget allocations and personnel.

District leadership. Motivating and coordinating the intra-disciplinary efforts described above requires the leadership of district administration. Creating equity in gifted programs also requires investment of time and resources. District leaders demonstrate commitment to a cause through budget allocations and personnel.

Results of the IEA-P suggest that educators who make these efforts will receive support from the public. IEA-P respondents from all backgrounds reported that they want gifted programs to be ubiquitous as long as gifted children in poverty and gifted children of color have equal access to services. They do not see gifted education as a problem, but rather, as part of a solution. Gifted education, in their view, is a tool to help the arc of the moral universe bend toward justice for gifted children who are black, brown, or impoverished.

References

Baldwin, A. Y. (1977). Baldwin Identification Matrix for the identification of gifted and talented students. East Aurora, NY: Trillium.

Center for Community Change (2017). Medicaid messaging. Retrieved October 3, http://communitychange.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Medicaid-Messaging.pdf

Coleman, M. R., & Shah-Coltrane, S. (2010). U-STARS~PLUS: Science & literature connections. Arlington, VA: Council for Exceptional Children.

Cowles, M., & Daniel, K. B. (1968). The effects of an enrichment program for disadvantaged high school pupils. The High School Journal, 52, 83-88.

Dorfman, D., Wallack, L., & Woodruff, K. (2005). More than a message: Framing public health advocacy to change corporate practices. Health Education and Behavior, 32 , p. 320-336.

Editorial Comment: Investing in Negro Brains. (1935). The Journal of Negro Education, 4, 153-155. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2292328

Gallagher, S. A. (2000). Project P-BLISS: An experiment in curriculum for gifted disadvantaged high school students. NASSP Bulletin, 84(615), 47-57.

Gallagher, S. A., & Gallagher, J. J. (2013). Using Problem-based Learning to explore unseen academic potential. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-based Learning, 7, 111-131.

Gallagher, S. A. (2007). The National Assessment of Education Progress: What the NAEP can—and can’t—report about gifted students. In F. A. Dixon (Ed.), Programs and services for gifted secondary students: A guide to recommended practices (p. 73-84). Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

Gavin, M. K., Casa, T. M., Adelson, J. L., Carroll, S. R., Sheffield, L. J., & Spinelli, A. M. (2007). Project M3: Mentoring mathematical minds—A research-based curriculum for talented elementary students. Journal for Advanced Academics, 18, 566-585.

Goings, R. B., & Ford, D. Y. (2018). Investigating the intersection of poverty and race in gifted education journals: A 15-year analysis. Gifted Child Quarterly, 62, 25-36.

Grissom, J. A., & Redding, C. (2016). Discretion and disproportionality: Explaining underrepresentation of high-achieving students of color in gifted programs. AERA Open, 2, 1-25.

Hamilton, R., McCoach, D. B., Tutwiller, M. S., Siegle, D., Gubins, J., Callahan, C. M., Brodersen, A. V., & Mun, R. U. (2018). Disentangling the roles of institutional and individual poverty in the identification of gifted students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 62, 6-24.

Jenkins, M. D. (1943). Case studies of Negro children of IQ 160 and above. Journal of Negro Education, 12, 159-166.

Klugman, J. (2013). The Advanced Placement arms race and the reproduction of educational inequality. Teachers College Record, 115(5), 1-34.

Lamprey, B. D., Dion, G. S., & Donahue, P. L. (2009). NAEP 2008: Trends in academic progress [NCES 2009-479]. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

Maker, C. J. (2001). DISCOVER: Assessing and developing problem solving. Gifted Education International, 15, 232-251.

Miley, J. F. (1975). Promising practices: Teaching the disadvantaged gifted. Ventura, CA: Ventura County Schools.

Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Clarenbach, J. (Eds.) (2012). Unlocking emergent talent: Supporting high achievement of low-income, high- ability students. Washington, DC: National Association for Gifted Students.

Plucker, J. A., Hardesty, J., & Burroughs, N. (2013). Talent on the sidelines: Excellence gaps and America’s persistent talent underclass. Storrs, CT: Center for Education Policy Analysis, University of Connecticut. Retrieved from http://cepa.uconn.edu/mindthegap.

Plucker, J. A., & Peters, S. J. (2018). Closing poverty-based excellence gaps: Conceptual, measurement, and educational issues. Gifted Child Quarterly, 62, 56-67.

Kennedy, J. F. (1963, June). Radio and television report to the American people on civil rights. Retrieved from https://www.jfklibrary.org/archives/other-resources/john-f-kennedy-speeches/civil-rights-radio-and-television-report-19630611.

Riessman, F. (1963). The culturally deprived child: A new view. Education Digest, 29(3), 12-22.

Robinson, A., Adelson, J. L., Kidd, K. A., & Cunningham, C. M. (2018). A talent for tinkering: Developing talents in children from low-income households. Gifted Child Quarterly, 62, 130- 144.

Robinson, M. L., & Meenes, M. (1947). The relationship between test intelligence of third grade Negro children and the occupations of their parents. Journal of Negro Education, 16, 136–141.

Shaklee, B. D. (1992). Identification of young gifted students. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 15, 134-144.

Theman, V., & Witty, P. (1943). Case studies and genetic records of two gifted Negroes. The Journal of Psychology, 15, 165–181.

Tisdall, W. J. (1968). A high school for disadvantaged students of high academic potential. The High School Journal, 52(2), 51-61.

VanTassel-Baska, J. (2018). Achievement unlocked: Effective curriculum interventions with low- income students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 62, 68-82.

VanTassel-Baska, J., & Stambaugh, T. (Eds.) (2007). Overlooked gems: A national perspective on low-income promising learners. Washington, DC: National Association for Gifted Children.

Wyner, J., Bridgeland, J., & Diiulio, J. (2007). Achievement trap: How America is failing millions of high-achieving students from lower- income families . Lansdowne, VA: Jack Kent Cooke Foundation.