Gifted Education Among the Public’s Education Priorities

A majority of the public shares a common understanding that a gifted child has advanced potential to learn, but not necessarily demonstrated achievement. The public also understands that educating a gifted child to achieve her full potential requires extra educational resources. Yet gifted education is one part of a multifaceted education system, and while all the parts of the system should work together, limited resources often force them into competition. To be effective, public policy initiatives require an understanding of the public’s sense of urgency around particular issues both singly and in relation to each other. The public supports gifted education when presented as an isolated issue, but where does it fall among priorities for education, when all of public education is overwhelmed with needs and chronically underfunded?

Gifted Education in Context: Grading K-12 Public Schools.

A series of questions on the IEA-P sought to determine where gifted education stands relative to other issues in education. The first questions in this section of the poll asked IEA-P respondents to grade public schools on a scale from A to F on their effectiveness meeting the needs of (1) all students, low-income students, (3) students with learning disabilities, and (4) gifted students.

Grades for public education’s effectiveness in addressing the needs of all students, low-income students, and students with learning disabilities. I EA-P respondents’ grades reflect a generally bleak view of public education in America; they parallel the answers to a similar question posed to respondents in the 2016 PDK/Gallup poll (Table 2.1). Only 5% of IEA-P respondents gave an A to public schools for addressing the needs of students with learning disabilities, 3% gave an A for addressing the needs of low-income students and 2% awarded an A for addressing the needs of all students. Far higher proportions of respondents gave a B for services provided to each group of students, and even more awarded a C.

Fewer than 25% gave the public schools an A or B combined for addressing the needs of all students and for students with learning disabilities, and only 17% awarded an A or B combined for addressing the needs of low-income students. For each of these three groups, the proportion of respondents who awarded a D or F combined equaled or exceeded the proportion who awarded an A or B combined.

Grades for addressing the needs of gifted students. Grades awarded to public schools for how well they addressed the needs of gifted children were consistently far better than the grades awarded for addressing the needs of other groups of children. Among all respondents, 21% awarded an A to public schools for their effectiveness in meeting the needs of gifted students, regardless of the term used, five times the rate that A grades were assigned to public education overall. Fifty-six percent awarded either an A or B, combined (Figure 2.1), and only 15% awarded a D or F grade.

Impact of varying terminology. The public was most likely to give the public schools an A when asked about addressing the needs of “Gifted” students (21%), followed by “High-Achieving” and “High- Potential” students (16% each). The public was least likely to award an A when asked to grade the public school’s success in serving “Highly-Able” students (12%), but even this was twice the number of A grades awarded for services to students with learning disabilities (5%) (Table 2.1).

Percentage of Responses to: “Generally Speaking, How Good of a Job Do You Think America's K-12 Public Schools Are Doing Addressing the Needs of ‘x’ Students?” (Q18-19)

|

IEA-P |

|||||

|

PDK/Gallup 2016 a |

All Students |

Low-Income |

Learning Disabilities |

Gifted b |

|

|

Grade |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

|

A&B |

24 |

22 |

17 |

24 |

56 |

|

A |

4 |

2 |

3 |

5 |

21 |

|

B |

20 |

20 |

14 |

19 |

35 |

|

C |

41 |

53 |

36 |

38 |

28 |

|

D |

20 |

19 |

31 |

28 |

11 |

|

F/Fail |

7 |

6 |

16 |

9 |

5 |

|

Don’t know |

8 |

N/A |

|||

Notes. Respondent n = 1414 for All Students, Low-Income Students, and Students with Learning Disabilities. At the 95% confidence level the standard error of measure for the entire sample is ±2.51%. It is ±6.21% among Opinion Elites, ±3.73% among Parents, ±6.03% among Blacks, ±5.81% among Hispanics, and ±3.33 among Whites

a PDK=Phi Delta Kappan. PDK/Gallup Poll respondents answered the question “What grade would you give the public schools nationally?” Starr (2016), n=1221

b Gifted = Split Sample C, n= 471. At the 95% confidence level the standard error of measure for Split Sample C is ±4.52.

Consistent with their grading patterns for other groups of students, IEA-P respondents were much more likely to award a B instead of an A to public schools, regardless of the term used. While services for “Gifted” students were most likely to receive an A grade (21%), services for “Highly-Able” students received the most B grades (44%).

Over half of the sample awarded an A or a B combined to public schools for addressing the needs of students who are “Gifted,” “Highly-Able,” or “High-Achieving” (56% each), “Gifted and Talented” or “High-Potential” (53% each), or “High-Performing” (51%). The public was least likely to award an A or a B, separately or combined, for addressing the needs of “Genius” students (14% A, 32% B, 46% combined).

IEA-P respondents believed that the public schools were doing a better job addressing the needs of gifted students than the needs of all students, low-income students, or students with learning disabilities. These findings suggest that the public is relatively unaware of the status of gifted programs around the country and operates under the misconception that, while gifted students may not have all the resources they require, public schools are doing a much better job addressing their needs, compared with other groups .

How Well are America's K-12 Public Schools Doing Addressing the Needs of These Students?

Figure 2.1. Percentage of A and B grades awarded to public schools for meeting the needs of all students, low-income students, students with learning disabilities, and gifted students (described by varied terms).

Education Influencers. Opinion Elites were most likely to award an A or a B to public schools for addressing the needs of “High-Achieving” (68%) and “High- Performing” (63%) students and least likely to award them for addressing the needs of “Gifted” (56%)or “High-Potential” (51%) students. Parents gave schools high grades for gifted education compared to services for students with learning disabilities or low-income students; however, they were less likely to award an A or a B for gifted education than other analysis groups. Only two terms received an A or a B combined from 50% of Parents, “High-Performing” (57%) and “Advanced Learner” (53%). Parents were least likely to award an A or a B to schools for services provided to students with “High-Potential” (42%).

Racial/Ethnic Groups. Black, Hispanic, and White respondents answered differently to the various terms when assigning grades (Table 2.2). In general, schools were more likely to receive a B instead of an A, but there were some exceptions.

These findings suggest that the public is relatively unaware of the status of gifted programs around the country and operates under the misconception that, while gifted students may not have all the resources they require, public schools are doing a better job addressing their needs than the needs of other students.

“A” grades awarded by racial/ethnic group. In general, Black respondents were the most likely to award an A, regardless of term:

- Between 25-36% of Black respondents awarded an A to public schools with respect to all terms except “Highly-Able,” and “High-Potential”;

- The only time 25% of Hispanics gave an A to schools was for the term “High-Achieving.” Only 9% of Hispanics awarded an A for schools for serving “Highly-Able” students;

- Schools received an A from 20% of White respondents for the term “Gifted” (20%). Fewer White respondents awarded an A for every other term, with only 10-12% awarding an A for most terms.

Across terms and groups, the schools were least likely to receive an A from Hispanic respondents with reference to “Highly-Able” students (9%), and most likely to receive an A from Black respondents with reference to “Gifted” students (36%).

Percentage of IEA-P Respondents Awarding A, B, and A&B Combined to Services to Gifted Students by Race/Ethnicity, Race/Ethnicity x Income, and Education Influencers (Q19)

| Race/Ethnicity | Race/Ethnicity x Income | Education Influencers | |||||||||||||

| White | Hispanic | Black | |||||||||||||

| Total | White | Hisp | Black | <$50k | $50k+ | <$50k | $50k+ | <$50k | $50k+ | OE | Parents | ||||

|

|

Weighted n: |

471 |

329 |

52 |

59 |

142 |

182 |

23 |

28 |

26 |

31 |

14 |

141 |

||

|

Unweighted n: |

471 |

275 |

98 |

76 |

89 |

182 |

38 |

60 |

36 |

38 |

82 |

241 |

|||

| Term |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

% |

|||

| Gifted | |||||||||||||||

|

A |

21 |

20 |

10 |

36 |

27 |

16 |

8 |

12 |

37 |

34 |

23 |

15 |

|||

|

B |

35 |

41 |

25 |

22 |

33 |

47 |

23 |

28 |

21 |

24 |

33 |

33 |

|||

|

A&B |

56 |

61 |

35 |

58 |

60 |

63 |

31 |

40 |

58 |

58 |

56 |

48 |

|||

|

Highly-Able Students |

|||||||||||||||

|

A |

12 |

12 |

9 |

17 |

14 |

9 |

9 |

10 |

13 |

18 |

14 |

8 |

|||

|

B |

44 |

46 |

35 |

43 |

39 |

52 |

38 |

33 |

31 |

56 |

46 |

37 |

|||

|

A&B |

56 |

58 |

44 |

60 |

53 |

61 |

47 |

43 |

44 |

74 |

60 |

45 |

|||

| High-Potential | |||||||||||||||

|

A |

16 | 16 | 12 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 15 | 9 | 26 | 8 | 15 | 12 | |||

|

B |

37 |

39 |

36 |

38 |

38 |

41 |

40 |

33 |

27 |

50 |

36 |

30 |

|||

|

A&B |

53 |

55 |

48 |

54 |

54 |

56 |

55 |

42 |

53 |

58 |

51 |

42 |

|||

|

Gifted and Talented |

|||||||||||||||

|

A |

13 |

10 |

17 |

26 |

10 |

11 |

19 |

15 |

32 |

21 |

23 |

10 |

|||

|

B |

40 |

39 |

43 |

31 |

37 |

41 |

29 |

53 |

23 |

37 |

39 |

35 |

|||

|

A&B |

53 |

49 |

60 |

57 |

47 |

52 |

48 |

68 |

55 |

58 |

62 |

45 |

|||

|

High-Achieving Students |

|||||||||||||||

|

A |

16 |

12 |

25 |

29 |

14 |

12 |

32 |

20 |

29 |

33 |

30 |

14 |

|||

|

B |

40 |

41 |

40 |

33 |

40 |

42 |

25 |

51 |

32 |

32 |

38 |

37 |

|||

|

A&B |

56 |

53 |

65 |

62 |

54 |

54 |

57 |

71 |

61 |

65 |

68 |

51 |

|||

|

Genius |

|||||||||||||||

|

A |

14 |

11 |

18 |

30 |

11 |

10 |

26 |

13 |

30 |

31 |

23 |

13 |

|||

|

B |

32 |

31 |

33 |

30 |

32 |

30 |

31 |

37 |

27 |

33 |

33 |

34 |

|||

|

A&B |

46 | 42 | 51 | 60 | 43 | 40 | 57 | 50 | 57 | 64 | 56 | 47 | |||

| High-Performing | |||||||||||||||

|

A |

13 |

11 |

14 |

26 |

9 |

12 |

16 |

14 |

25 |

30 |

27 |

13 |

|||

|

B |

38 |

37 |

47 |

30 |

29 |

42 |

40 |

53 |

35 |

26 |

36 |

44 |

|||

|

A&B |

51 |

48 |

61 |

56 |

38 |

54 |

56 |

67 |

60 |

56 |

63 |

57 |

|||

|

Advanced Learners |

|||||||||||||||

|

A |

13 |

11 |

15 |

25 |

10 |

11 |

18 |

14 |

22 |

29 |

21 |

13 |

|||

|

B |

36 |

34 |

45 |

42 |

33 |

36 |

56 |

38 |

41 |

44 |

38 |

40 |

|||

|

A&B |

49 |

45 |

60 |

67 |

43 |

47 |

74 |

52 |

63 |

73 |

59 |

53 |

|||

Notes. Hisp = Hispanics, OE= Opinion Elites. The IEA-P respondent group was randomly assigned to one of three groups; each group responded to either two or three terms (n = 471 for split samples C and D, n=472 for split sample E. See Appendix B, Table B3 for measurement error). Each group was presented with one term explicitly mentioning giftedness or genius and one or two terms designed to suggest advanced ability through the use of “High-x.” Split Sample C = Gifted, Highly-Able, High-Potential; Split Sample D= Gifted and Talented, High-Achieving; Split Sample E = Genius, High-Performing, Advanced Learners. Race/Ethnicity does not include respondents who selected more than one race. Race/Ethnicity x Income does not include respondents who selected “Prefer Not to Indicate.”

A Deeper Look

IEA-P results reveal a broadly held misconception among the public that the K-12 public schools are doing an above- average job providing an appropriate education for America’s best and brightest. Advocates for gifted students who are familiar with the patchwork quilt of policies across the nation will recognize this as grade inflation, especially relative to grades awarded for other areas of education. Only four states have a fully funded mandate to serve gifted students. At least 10 states still have no mandate for gifted education services. Some states with mandates for gifted education provide little or no funding to districts, making it difficult to provide high-quality programs (NAGC, 2015). Consequently, geography is a pivotal factor determining whether or not a gifted child has access to services. Gifted children who live in states with a funded mandate are most likely to receive services, while children who live in states without a mandate or funding are more likely to havetheir needs overlooked. Unlike the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and the Title 1 program, federal dollars for gifted education provided through the Jacob K. Javits Gifted and Talented Act fund a national center and a handful of research and development projects. Although the center and projects produce useful research and materials, no federal money for gifted education goes directly to school districts or to state governments to distribute to school districts.

Above average grades awarded by racial/ethnic group. Markedly different patterns emerged among racial/ethnic groups when looking at patterns of awarding “above average” A and B combined. For some terms, more Hispanic and Black respondents awarded high grades:

- “Advanced Learners”: Over 60% of Black and Hispanic respondents awarded an A or a B to schools compared to 45% of White respondents;

- “High-Achieving”: Over 65% of Hispanic and 62% of Black respondents awarded an A or a B to schools compared to 53% of White respondents;

- “Gifted and Talented”: 60% of Hispanic and 57% of Black respondents awarded an A or a B to schools, compared to 49% of White respondents.

The American public expressed a deep desire for strong public schools, and nothing was more important to them than high-quality teachers.

For other terms, Hispanics were the least likely to award above average grades:

- “Gifted”: 61% of White and 58% of Black respondents awarded an A or a B to schools compared to 35% of Hispanic respondents; and

- “Highly-Able”: 60% of Black and 58% of White respondents awarded an A or a B to schools compared to 44% of Hispanic respondents.

Across terms and groups, the schools were least likely to receive an A or a B from Hispanic respondents with reference to “Gifted” students (35%), and most likely to receive an A or a B from Black respondents with reference to “Advanced Learners” (67%).

One Among Many: Concern for Gifted Education in Relation to Other Education Issues

Public schools receive relatively good grades for addressing the needs of gifted students, at least compared to the grades they receive for addressing the needs of other students. These grades suggest that gifted education might not rise to the level of a significant issue when juxtaposed with other pressing needs facing schools. To assess whether this was the case, all IEA-P respondents answered a series of questions which assessed their level of concern about gifted education relative to other educational issues. The other issues included in this question were selected based on their prominence in national media and among education professionals: (1) inadequate funding to hire qualified teachers, (2) inadequate funding for schools in low-income areas, (3) inadequate funding for students with learning disabilities, (4) inadequate spending on STEM or on (5) arts education, and (6) time spent on accountability tests. For each item, respondents were asked to respond on a four-point scale ranging from “Not a Problem at All” to “One of the Biggest Problems in Education.” Respondents answered each item individually rather than rank-ordering the seven issues; item order was randomized to minimize response bias.

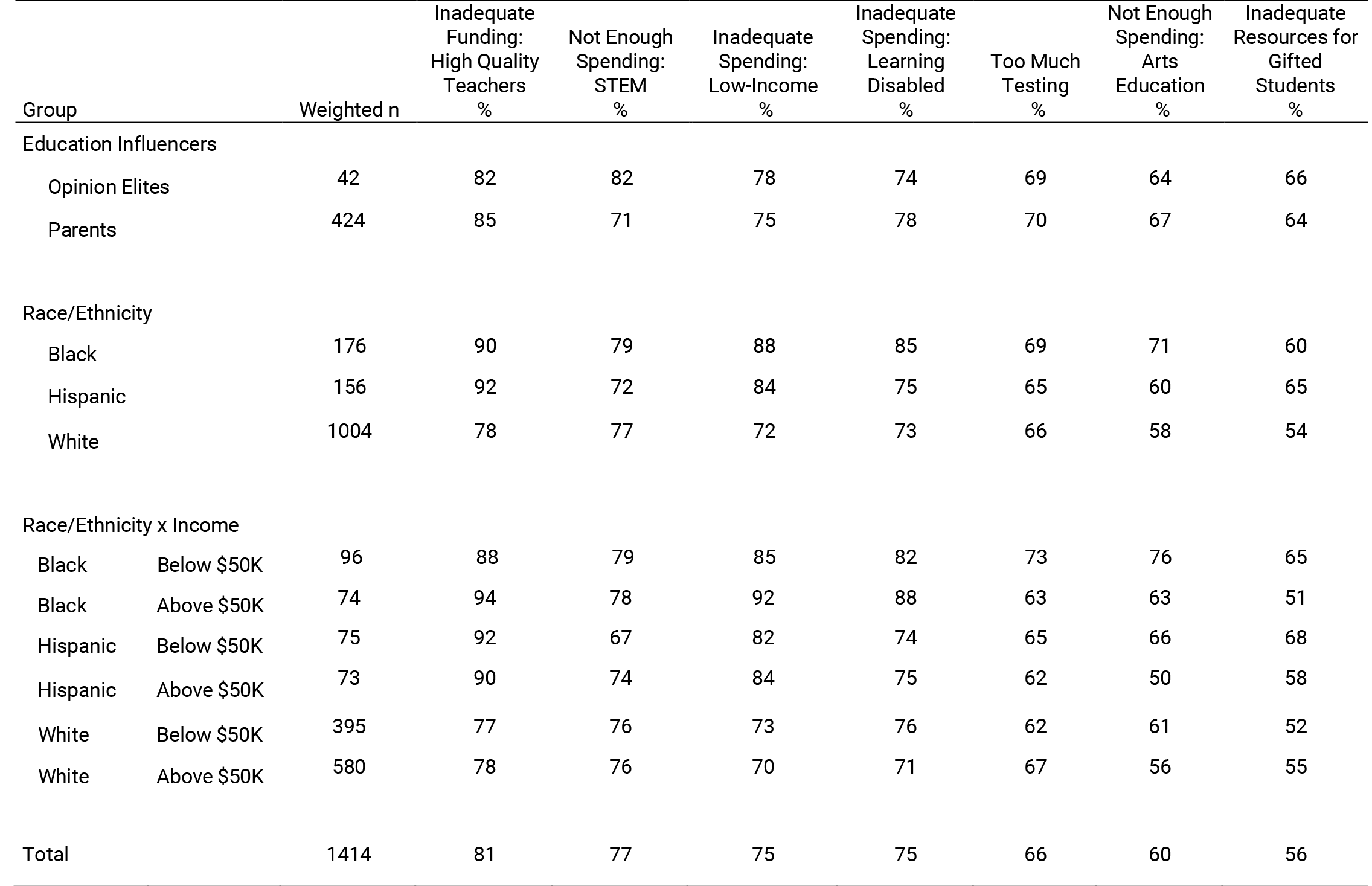

Percentage of IEA-P Respondents who Consider Specific Educational Issues “A Problem, but Not the Biggest Problem” or “One of the Biggest Problems in Education,” Combined (Q20)

Notes. At the 95% confidence level the standard error of measure for the entire sample is ±2.51%. It is ±6.21% among Opinion Elites,±3.73% among Parents, ±6.03% among Blacks, ±5.81% among Hispanics, and ±3.33 among Whites. Race/Ethnicity does not include respondents who selected more than one race. Race/Ethnicity x Income does not include respondents who selected “Prefer Not to Indicate.”

How Significant Are These Problems?

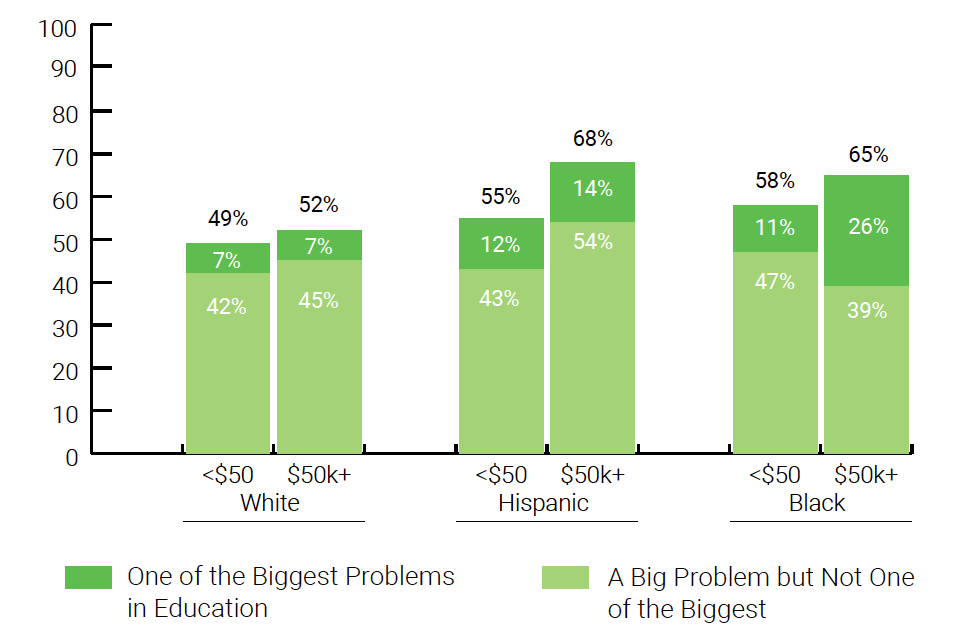

Figure 2.2. Percentage of responses to “How big of a problem for our education system is (x)?”

Public concern over high profile issues in education. The American public expressed a deep desire for strong public schools, and nothing was more important to them than high-quality teachers. Fully 80% of respondents considered inadequate funding to hire high-quality teachers a problem, and 43% believed it was one of the biggest problems facing public education (Figure 2.2, Table 2.3).

Inadequate funding for STEM education also provoked concern, with 77% of respondents indicating that it was either “A Big Problem” or “One of the Biggest Problems” facing public schools. A similar percentage (75%) reported that inadequate funding for low-income schools and students with learning disabilities was a problem, and accountability testing was considered excessive by 66% of respondents. Six in ten respondents believed that inadequate funding for arts education was either a big problem or one of the biggest problems facing education.

How Significant is This Problem: Lack of Resources for Gifted Students

Figure 2.3. Percentage of concern in response to “How big a problem to education is inadequate resources for gifted students?”

Public concern over resources for gifted education. Despite the relatively high grades public schools received for addressing the needs of gifted students, 57% of IEA-P respondents indicated that inadequate resources for gifted students were a problem. The number of people who thought that the lack of gifted education resources was a sizable problem exceeded the number of parents of gifted students, the number of parents with school-aged children, and even the number college graduates polled. Thirteen percent of the overall respondent group reported that lack of resources for gifted education was one of the most significant problems in education (Figure 2.3).

Education Influencers. Approximately two-thirds of Opinion Elites and Parents reported that a lack of resources in gifted education was a problem (Figure 2.4).

How Significant is This Problem: Lack of Resources for Gifted Education?

Figure 2.4. Percentage of Opinion Elites and Parents who reported that lack of resources for gifted is a big problem or one of the biggest problems in education.

Racial/Ethnic Groups. Black and Hispanic respondents were much more likely than White respondents to think that inadequate resources for gifted students was a problem, including 60% of Black respondents and 65% of Hispanics.

Over 50% of each race/ethnicity-by-income demographic group agreed that inadequate gifted education resources were either a “A Big Problem” or “One of the Biggest Problems” facing public education. Only 7% of higher-income White respondents, but 26% of higher-income Black respondents considered resources for gifted education “One of the Biggest Problems” in education (Figure 2.5). Between 64-68% of Opinion Elites, Parents, and lower-income Black and Hispanic respondents reported that inadequate resources for gifted students were one of the biggest problems facing public education.

Hispanics were especially concerned about funding for gifted education compared to other issues. Similar numbers of lower-income Hispanics reported concern about funding for STEM (67%), the arts (66%), excessive accountability testing (65%) and inadequate funding for gifted education (68%). More higher-income Hispanics were concerned about funding for gifted education (58%) than for arts education (50%). Higher-income White respondents were also equally likely to report concern about arts funding (56%) and gifted education funding (55%) (Table 2.3).

America Agrees: Inadequate Resources for Gifted Education IS a Problem. Is Remedying the Problem a Public Priority?

Although concern over funding for gifted education did not rise to the same levels of concern as high- profile issues like teacher quality or STEM education, a majority of Americans think that inadequate funding for gifted education is a problem for public schools. Some groups believe that funding gifted education is as pressing an issue as funding for the arts or STEM. The next question addressed by the IEA-P was whether they thought the problem was significant enough to take priority over other issues with the question, “Compared to other priorities in education, how big of a priority should it be to ensure that (x) students have the resources they need?” This question also included a second assessment of the impact of terminology on respondent answers. 1 [9]

How Significant is This Problem: Lack of Resources for Gifted Education?

Figure 2.5. Percentage of responses indicating lack of resources for gifted education is a big problem or one of the biggest problems, by race/ethnicity and income.

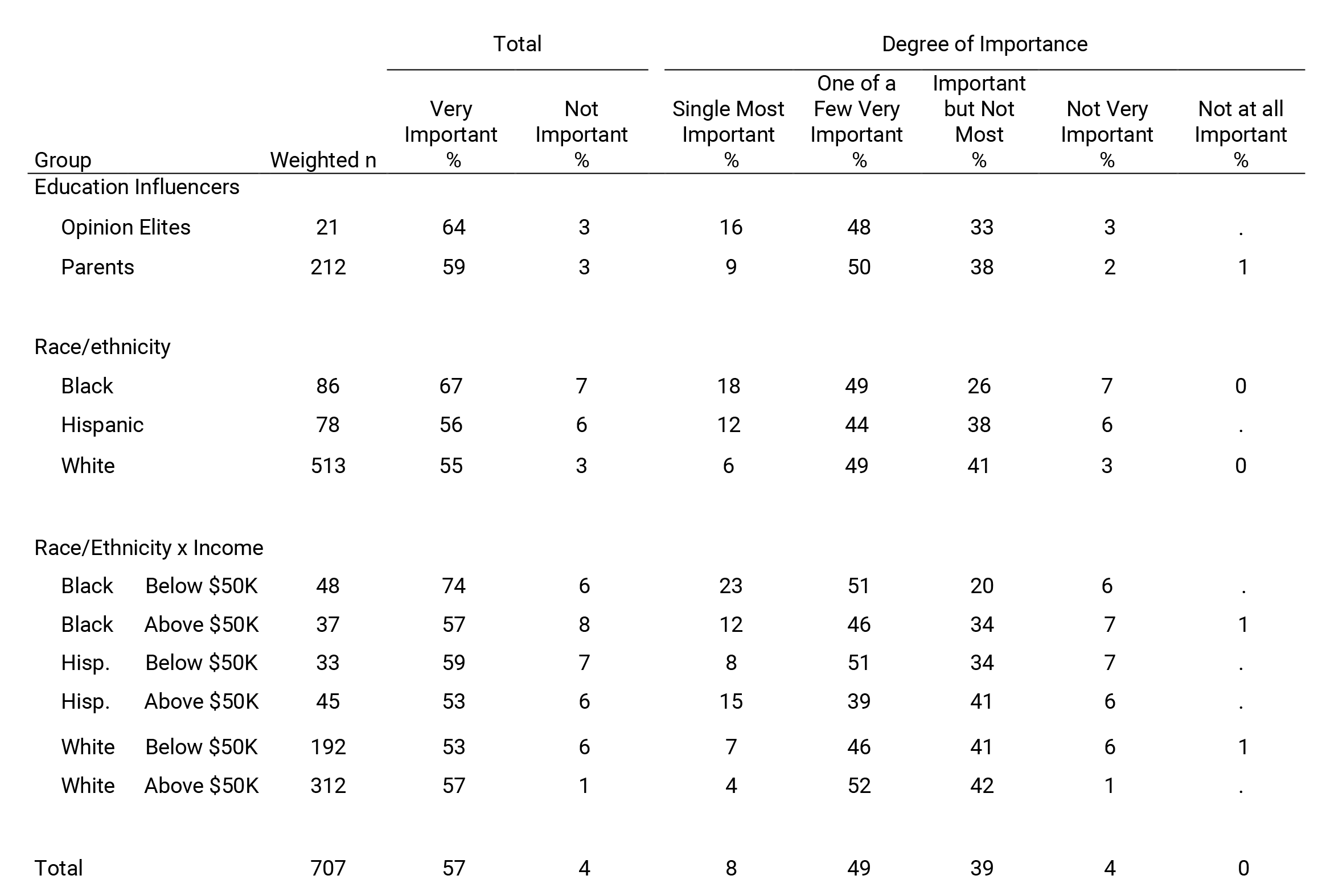

Does the public think providing resources for “gifted” students is a priority compared to other needs? Fifty-eight percent of the split sample who answered the question with respect to “Gifted” students responded that ensuring appropriate resources was either “One of a Few Very Important Priorities” or the “Single Most Important” priority in education. Another 39% indicated that it was important, although not one of the most important priorities (Figure 2.6). Only 4% of respondents answered that ensuring appropriate resources for gifted students was “Not Very Important” and almost no one thought that resources for gifted students was “Not Important at All.”

Education Influencers. Sixty-four percent of Opinion Elites and 59% of Parents thought that ensuring gifted students have appropriate resources was an important issue for public education. Fewer than five percent of either group reported that the problem was “Not Very Important” (Table 2.4).

Percentage of Responses to “Compared to Other Priorities in Education, How Big of a Priority Should be to Ensure That Gifted Students Have the Resources They Need?” (Q31R1)

Notes. Split Sample X. At the 95% confidence level the standard error of measure for the entire sample is ±2.51%. It is ±6.21% among Opinion Elites, ±3.73% among Parents, ±6.03% among Blacks, ±5.81% among Hispanics, and ±3.33 among Whites. Hisp. = Hispanic. "." = too small to calculate. Race/Ethnicity does not include respondents who selected more than one race. Race/Ethnicity x Income does not include respondents who selected “Prefer Not to Indicate.”

Racial/Ethnic Groups. Once again, over 50% of each racial/ethnic and income group gave answers supportive of gifted education, responding that K-12 schools should place a priority on providing gifted students with the resources they need. Gifted education was most likely to be considered important among low-income Black respondents, 74% of whom reported that gifted education was a priority, and 24% of whom considered providing resources for gifted education the “Single Most Important Priority” for public education.

Investment in gifted education went far beyond an intellectual or social “elite”; over 60% of both the higher- and lower- income groups indicated support for providing resources for gifted children. Fewer than 10% of each group reported that providing resources for gifted education was “Not Very Important.” Only a handful of respondents believed that providing gifted students with resources they need was “Not at All Important” as an educational priority.

How Much of a Priority is it to Ensure Gifted Students Have the Resources They Need?

Figure 2.6. Percent of respondents who consider resources for gifted students a priority, relative to other concerns.

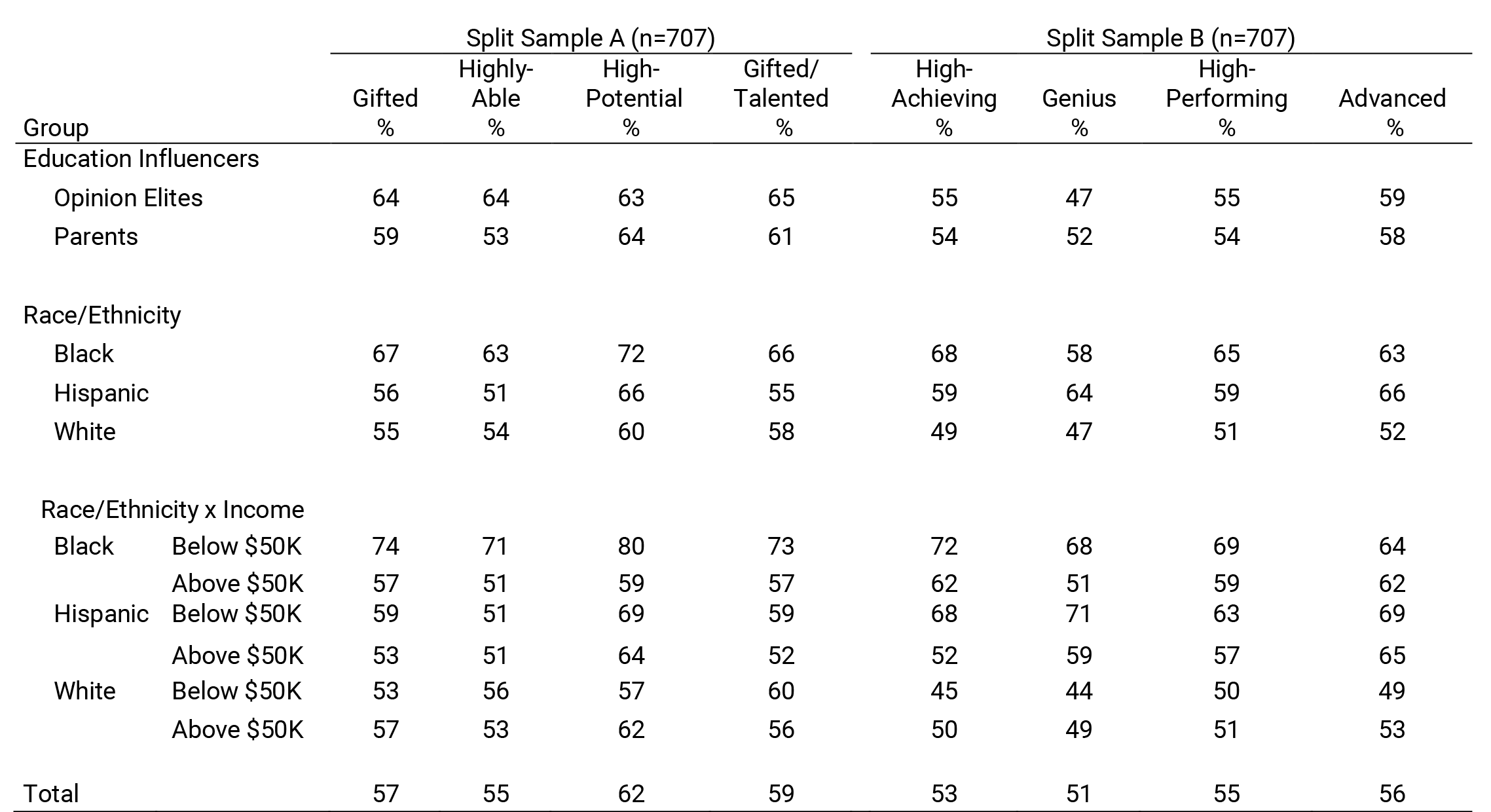

The impact of terminology on priorities. Public support for providing resources for gifted students was high regardless of the term used, although the terms “High-Potential,” “Gifted and Talented,” and “Gifted” elicited the highest level of support (Table 2.5). Across terms, 7-9% of the public reported that providing resources for gifted students was the “Single Most Important” priority in education, and between 51-58% of the public thought it was either the “Single Most Important Priority” or “One of a Few Very Important Priorities.” As illustrated in Figure 2.7, the public supports providing services to both gifted and high-achieving students, even though many associate the two terms with different groups of children.

Investment in gifted education went far beyond an intellectual or social “elite”; over 60% of both the higher- and lower- income groups indicated support for providing resources for gifted children.

Education Influencers. Between 63-65% of Opinion Elites believed that providing resources for “Gifted,” “Gifted and Talented,” “Highly-Able,” or “High-Potential” students was either the single most important or one of the few important priorities in public education. They responded much more favorably to these four terms than to “High-Achieving,” “Genius,” “High-Performing,” or “Advanced,” none of which received support from more than 60% of the subgroup. Parents were most likely to respond that schools should place a priority on providing “High-Potential” or “Gifted and Talented” students with the resources they need.

Racial/Ethnic Groups. A majority of respondents thought that providing resources for gifted students was an important priority; however, the overall results masked sizable differences among demographic groups. Black respondents were most likely to consider gifted education a priority. Over 60% of Black respondents said gifted education was either the single most important priority or one of a few important priorities for all terms except one, “Genius” (58%). Seventy-two percent of Black respondents reported that ensuring resources for “High-Potential” students was an important priority.

Regardless of the term used, a majority of Hispanics considered ensuring resources for gifted students a priority, with especially high rates of support for “High-Potential” and “Advanced” students (66% each) as well as for “Genius” students (64).

The proportion of White respondents in support of ensuring services for gifted students ranged from 47-60%, and was consistently lower than the percent of Black respondents in support, regardless of the term used to describe gifted students. The proportion of White respondents in support of ensuring services for gifted students only reached 60% once, for “High-Potential” students.

Lower-income Black respondents voiced strong support for ensuring resources for gifted students, often at margins far beyond White, Hispanic, or higher-income Black respondents. Over 70% of lower-income Black respondents believed that providing resources for gifted students was an important priority across a majority of terms. The only two terms that did not prompt support from more than 70% of lower-income Black respondents were “Genius” at 68%, and “Advanced” at 64%. In many cases the proportion of lower-income Black respondents in support was 15-20% higher than other groups.

Percentage Responding to “Single Most Important Priority” and “One of A Few Important Priorities” Combined: “Compared to Other Priorities in Education, How Big of a Priority Should it be to Ensure That (x) Have the Resources They Need?” (Q31)

Notes. For subsample standard error of measure see Appendix B, Table B3. Race/Ethnicity does not include respondents who selected more than one race. Race/Ethnicity x Income does not include respondents who selected “Prefer Not to Indicate.”

Compared to Other Priorities, How Important are the Needs of These Students?

Figure 2.7. Percentage of those who consider gifted education “The Single Most Important” or “One of the Few Most Important” priorities, by term.1[10]

Synopsis

How the Public Grades K-12 Schools

The American public does not subscribe to many of the so-called “myths” of gifted education, however, one myth that still seems prevalent is that gifted education programs already possess the resources they need to educate the nations brightest students. Well over half of the individuals polled believed that gifted education is necessary and voiced support for providing resources for gifted students. However, when grading the K-12 schools, the public also reported thinking that schools are already doing a good job meeting the needs of gifted students, relative to other groups.

- IEA-P respondents’ grades of K-12 schools reflect a generally dim view of public education in America. Only 5% of IEA-P respondents gave an A to public schools for addressing the needs of students with learning disabilities, 3% gave As for addressing the needs of low-income students and 2% awarded As for addressing the needs of all students.

- IEA-P respondents generally believed that the public schools were doing a better job addressing the needs of gifted students than needs of all students, low-income students, or students with learning disabilities. The American public was more generous in awarding either an A or a B for services to gifted students, regardless of the term used for giftedness. The term “Gifted” received the highest number of As (21%), and “Highly-Able” the lowest (12%).

- Americans think that services for gifted students are adequate, even robust, awarding them an A or a B grade; here, public perception diverges with reality. The public seems uninformed about the absence of gifted programs in many states and inadequate funding nationwide. Correcting the public’s misconceptions about the availability of gifted programs is a necessary first step to advocacy to fill in the nation’s patchwork quilt of programs and policies for gifted students.

The Lack of Resources for Gifted Education is a Problem

Respondents’ answers to benchmark questions reveal substantial concern about the state of K-12 public education. They responded with trepidation about every issue presented in the poll, but nothing was more important to the public than the absence of funding for high-quality teachers. Concern about this issue was high among all respondents but particularly high among Black and Hispanic respondents, 90% of whom reported that lack of funding for high-quality teachers was either “A Big Problem” or “One of the Biggest Problems” in education.

- Teacher quality, STEM education, and educational equity for low-income students are common topics in national education news, so it is natural that the public responds to them with heightened concern. Moreover, issues such as teacher quality, STEM, the arts, and testing directly affect all students, regardless of ability, while the state of gifted education directly affects only a subset of students. Even so, 57% of the public believed that providing resources for gifted education was either “A Big Problem” or “One of the Biggest Problems” in education. This was both less concern than was expressed about more salient educational issues, and more concern than might be expected given the lack of exposure the public has to information about challenges in funding gifted education programs around the country.

- The public awarded relatively high grades to schools for addressing gifted students’ needs. Even so, the number of people who were concerned about the lack of gifted education resources and thought it was a sizable problem exceeded the number of parents of gifted students, the number of parents with school- aged children, and even the number college graduates polled.

The terms most likely to evoke support for ensuring resources, overall and within analysis subgroups, were:

“Gifted,” “Gifted and Talented,” and “High-Potential,”

Improving Gifted Education is a Priority

Judging from the responses of IEA-P respondents, the concern voiced by the American public translates into support for change. Many believe that providing gifted students with appropriate resources should be among the nation’s education priorities.

- Support was reported from over 50% of poll respondents regardless of the term used to describe giftedness and despite their differing interpretations of terms such as “Gifted” and “High-Achieving.” The terms most likely to evoke support for ensuring resources, overall and within analysis subgroups, were “Gifted,” “Gifted and Talented,” and “High-Potential.”

- A majority of every income and racial/ethnic group believed that lack of resources for gifted education was a problem and placed a high priority on addressing the problem. Over 50% of each race/ethnicity-by-income group agreed that inadequate gifted education resources were either a “Big Problem” or “One of the Biggest Problems” facing public education, indicating support for providing resources for gifted children that extends far beyond an elitist minority.

References

National Association for Gifted Children (2015). 2014-2015 State of the states in gifted education. Washington, DC: Author.