Public Concern Over Common Problems in Gifted Education

Change in public policy is the result of public concern over the status quo, accompanied by public support for an idea that resolves the concern. Changes in policies to improve education services for gifted students are unlikely without both public concern and support. For this reason, the next set of questions in the IEA-P assessed the extent of public concern over commonly cited problems within gifted education, and the extent of public support for specific recommendations which could resolve the problems. This series of questions also presented an opportunity to assess public opinion about specific elements of gifted education, as opposed to addressing “gifted education” as a whole. Results from questions about the public’s concerns are presented in this chapter; public support for specific program provisions is addressed in Chapter 5.

Public Concern over Common Problems in Gifted Education.

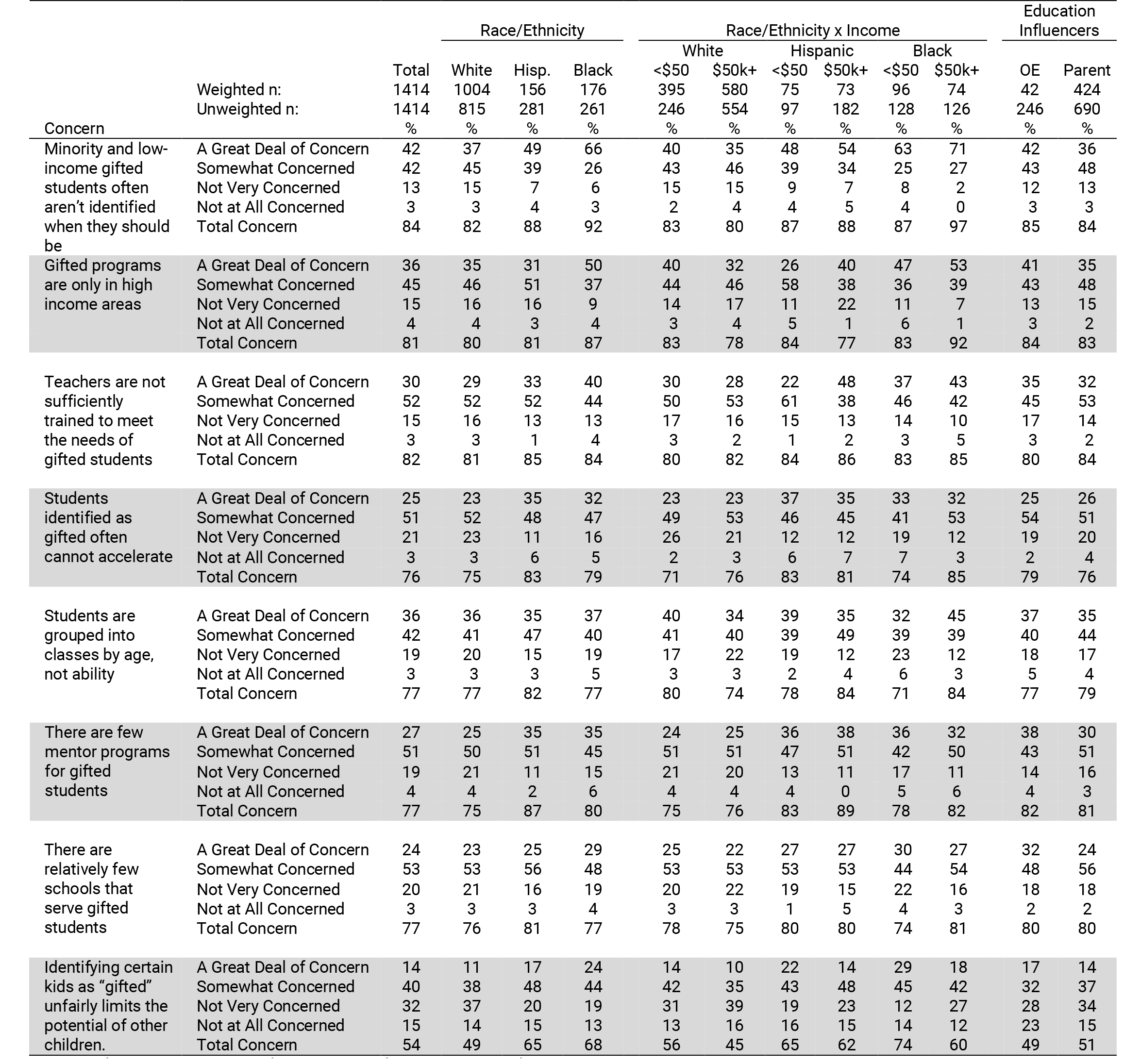

IEA-P respondents were asked to rate their level of concern about eight issues commonly cited as problems for gifted education (Figure 3.1). The eight topics were collapsed into four problem areas: (1) access for gifted students to high-quality gifted education programs, including inequitable identification and location of gifted programs; (2) teacher preparation in gifted education; (3) availability of program provisions for gifted students, including ability grouping, acceleration, schools for the gifted, and mentorship opportunities; and (4) inadvertent negative impacts of gifted education on other students (Figure 3.1). While a majority of respondents expressed concern about each topic, their answers clustered into three tiers: equal access to quality programs and teacher preparation evoked the most concern, followed by availability of program provisions, and then the impact gifted programs had on other students (Table 3.1, Figure 3.2).

Program features, and associated concerns addressed in the IEA-P.

|

Program Feature |

Concerns |

|

Access to high- quality gifted programs |

|

|

Teacher preparation in gifted education |

|

|

Gifted education program provisions |

|

|

Inadvertent negative impacts |

|

Figure 3.1. Program features, and associated concerns addressed in the IEA-P.

Access to high-quality gifted education programs. Equal access to quality programs was the issue most likely to arouse concern among IEA-P respondents. Taken as a whole, similar proportions of the American public were concerned about equitable identification practices and the disproportionate location of gifted education programs in higher- income neighborhoods.

Eighty-four percent of IEA-P respondents reported concern about the under-identification of low-income and minority gifted students, and 42% of the group reported that this issue concerned them “A Great Deal.” The public was also concerned that gifted programs were typically found in higher-income areas with 81% of the respondent group expressing either “Some” or “A Great Deal” of concern (Table 3.1).

Percentage of Response to: “Please Indicate how Much Each of the Following Concerns You Personally, If at All.” (Q42)

Notes. <$50 = Income under $50,000/year, $50k+ = Income $50,000 and above, OE = Opinion Elite, Hisp = Hispanics, Total Concern = the sum of A Great Deal of Concern plus Somewhat Concerned, “.” = too few observations to calculate. At the 95% confidence level the standard error of measure for the entire sample is ±2.51%. It is ±6.21% among Opinion Elites, ±3.73% among Parents, ±6.03% among Blacks, ±5.81% among Hispanics, and ±3.33 among Whites. Race/Ethnicity does not include respondents who selected more than one race. Race/Ethnicity x Income does not include respondents who selected “Prefer Not to Indicate.”

Public Response: How Much Do These Concern You Personally, If At All?

Figure 3.2. Percentage of respondents who reported “Some” or “A Great Deal” of concern about common problems in gifted education (Q42).

Education Influencers. Similar percentages of Opinion Elites and Parents indicated concern about under- identification of minority and low-income gifted students (85% of Opinion Elites and 84% of Parents), and the absence of gifted programs in low-income areas (84% of Opinion Elites and 83% of Parents). Opinion Elites were slightly more likely to report “A Great Deal” of concern about both issues: 42% of Opinion Elites and 36% of Parents indicated a great deal of concern about under-identification, and 41% of Opinion Elites and 35% of Parents reported a great deal of concern about the absence of gifted programs in low-income areas.

In the Poll…

75% indicated general concern over lack of funding for educating all low-income students.

81% reported concern about the tendency to put gifted programs in high income areas.

84% reported concern about underidentification of low-income and minority gifted students.

Racial/Ethnic Groups. At least 80% of each racial/ ethnic subgroup expressed either some concern or a great deal of concern about under-identification of minority and low-income gifted students (Figure 4.3). This concern was most frequently reported by Black respondents, 92% of whom expressed concern, followed by 88% of Hispanic and 82% of White respondents (Table 4.1). Hispanic and Black respondents were also most likely to report “A Great Deal of Concern” over identification practices, including 66% of Blacks and 49% of Hispanics, compared to 37% of White respondents. Higher- income Black respondents expressed almost unanimous concern (97%) over the failure to identify low-income and minority students.

Black and Hispanic respondents were more concerned about identification than they were about disproportionate location of gifted programs in higher-income areas. Among Black respondents, 66% were “A Great Deal” concerned about equitable identification while 50% were similarly concerned about program access. Among Hispanic respondents, 49% were “A Great Deal” concerned about identification and while 31% were very concerned about program access. White respondents reported equivalent levels of concern for identification and gifted program location; 82% reported concern about identification and 80% about program access (37% and 35% a great deal of concern, respectively) (Table 3.1).

Concern about adequate teacher preparation in gifted education. Early in the IEA-P, respondents voiced their desire for all classrooms to be led by well-qualified teachers (Chapter 3). In this section of the poll they indicated that preparation to teach gifted students is equally important.

When asked if they were concerned that “teachers are not sufficiently trained to meet the needs of gifted students,” 82% of the public said they were, including 30% who said they had “A Great Deal of Concern.” Only 3% of respondents were “Not at All Concerned” about the teacher preparation in gifted education.

In the Poll…

81% of the public reported concern over whether ALL schools had adequate funding to hire high-quality teachers.

82% indicated concern over teacher preparation to work with gifted students specifically.

86% support requiring training for teachers who work with gifted students.

Education Influencers. Parents were among the most likely to report concern over the training teachers receive to work with gifted students (85% “Some” and “A Great Deal” of concern combined). Opinion Elites were somewhat more likely than Parents to report “A Great Deal” of concern over teacher preparation in gifted education (37% Opinion Elites, 32% Parents).

Racial/Ethnic Groups. Concern about teacher preparation in gifted education exceeded 80% and of race/ethnicity, or race/ethnicity-by-income group. Higher-income Hispanic respondents were most likely to report concern (86%).

Discrepancies were observed in the magnitude education by racial/ethnic x income group. Black respondents were substantially more likely than Hispanic or White respondents to report a great deal of concern (40% Black, 33% Hispanic, 29% White). However, the largest within-group disparity was observed among Hispanics, with 48% of higher- income Hispanics but only 22% of lower-income Hispanics reporting a great deal of concern about teacher preparation in gifted education.

Concern over availability of recommended gifted program provisions. The American public was slightly more concerned about equitable access to quality gifted programs and teacher preparation to work with gifted students than they were about the availability of the specific gifted program provisions included in this poll. Even so, clear majorities of over 70% indicated concern over opportunities for students to be grouped by ability or accelerated, over the absence of specialized schools for gifted students, and over a lack of mentorship opportunities (see Figure 3.1, Table 3.1).

Ability grouping and acceleration. Among the four program provisions, the absence of ability grouping evoked the most concern, with 36% expressing a great deal of concern and another 42% reporting some concern that schools group students according to age instead of ability (Table 3.1). Concern over the absence of ability grouping, expressed by 78% of respondents, outstripped concern over any possible negative social-emotional impact of grouping, reported by 45% (Figure 3.3).

The absence of opportunities to accelerate evoked a similar concern. Seventy-five percent of the total respondent group indicating they had “A Great Deal” or “Some Concern” that gifted students were not allowed to accelerate (Table 3.1).

Education Influencers. Opinion Elites and Parents had similar response patterns when answering questions about program provisions. Opinion Elites and Parents were each marginally more likely to be concerned about access to mentorship programs and ability grouping than they were about opportunities for acceleration. Opinion Elites were somewhat more likely than Parents to report “A Great Deal of Concern” over the availability of mentorships (38% Opinion Elites, 30% Parents) and the availability of schools for the gifted (32% Opinion Elites, 24% Parents).

Public Response: How Much Do These Concern You Personally, If At All?

Figure 3.3. Percentage of respondents who reported “A Great Deal of Concern” over under-identification and lack of access to programs by racial/ethnic group.

Racial/Ethnic Groups. Concern that students were grouped by age instead of ability was high among racial/ethnic groups, led by higher-income Blacks and Hispanics (84% each), and lower-income Whites (80%). Higher-income Black respondents were mostly likely to report “A Great Deal” of concern (45%), and lower-income Blacks were least likely (32%).

Over 80% of Hispanics reported concern over gifted students’ ability to accelerate (83% higher-income and 81% lower-income) and were more likely than White respondents to report a great deal of concern (37% higher-income and 35% lower-income Hispanics, compared to 23% each for lower- and higher-income Whites). Among lower-income White respondents 71% reported concern that gifted students were unable to accelerate; this was lower than other subgroups but still nearly three-quarters of the subgroup.

Only a handful of respondents claimed that they were “Not at All Concerned” about the issues presented in this section of the poll—well under 10% of respondents, regardless of the question.

Hispanic and Black respondents were more likely than White respondents to express concern over a lack of mentorship programs. Hispanics were most likely to be concerned, especially higher-income Hispanics, 89% of whom reported being either “Somewhat” or “A Great Deal” concerned. Eighty percent of Black respondents and 75% of White respondents were concerned over the absence of mentorship opportunities.

Overt attitudes are sometimes affected by an underlying belief. For instance, support for issues like ability grouping may be affected by worry about the social and emotional impact of treating gifted students differently. However, slightly over half of the public understands that being with like-ability peers produces social and emotional benefits.

Figure 3.4. Percentage of response to “When it comes to accelerating gifted children (in special programs, or by advancing them to a higher-grade level), which concerns you more?”

Response patterns were repeated with respect to the availability of schools for the gifted. Concern over this issue was marginally higher among Hispanics, 81% of whom reported concern, than it was for White or Black respondents (76% and 77%, respectively). Among lower-income Black respondents, 30% were most likely to report “A Great Deal” of concern, while higher-income White respondents were least likely (22%).

Inadvertent negative impact on students in general education. Compared to the level of concern expressed over other issues in this section of the poll, IEA-P respondents were not overly concerned about whether identifying some students as gifted is unfair to students who are not identified. Although 54% were worried that identifying some students as gifted created unfair distinctions among students, the concern was comparatively modest. Only 14% were concerned “A Great Deal” about gifted education being unfair to others, far below the proportion who were “A Great Deal” concerned about equitable access to gifted programs (32%) or under- identification of minority and low-income gifted students (42%). Lower-income Hispanics and lower- income Blacks were most likely to express a great deal of concern about the impact of identifying some students as gifted and others not, but even these respondents were twice as likely to express concern over equitable identification and program access (Table 3.1).

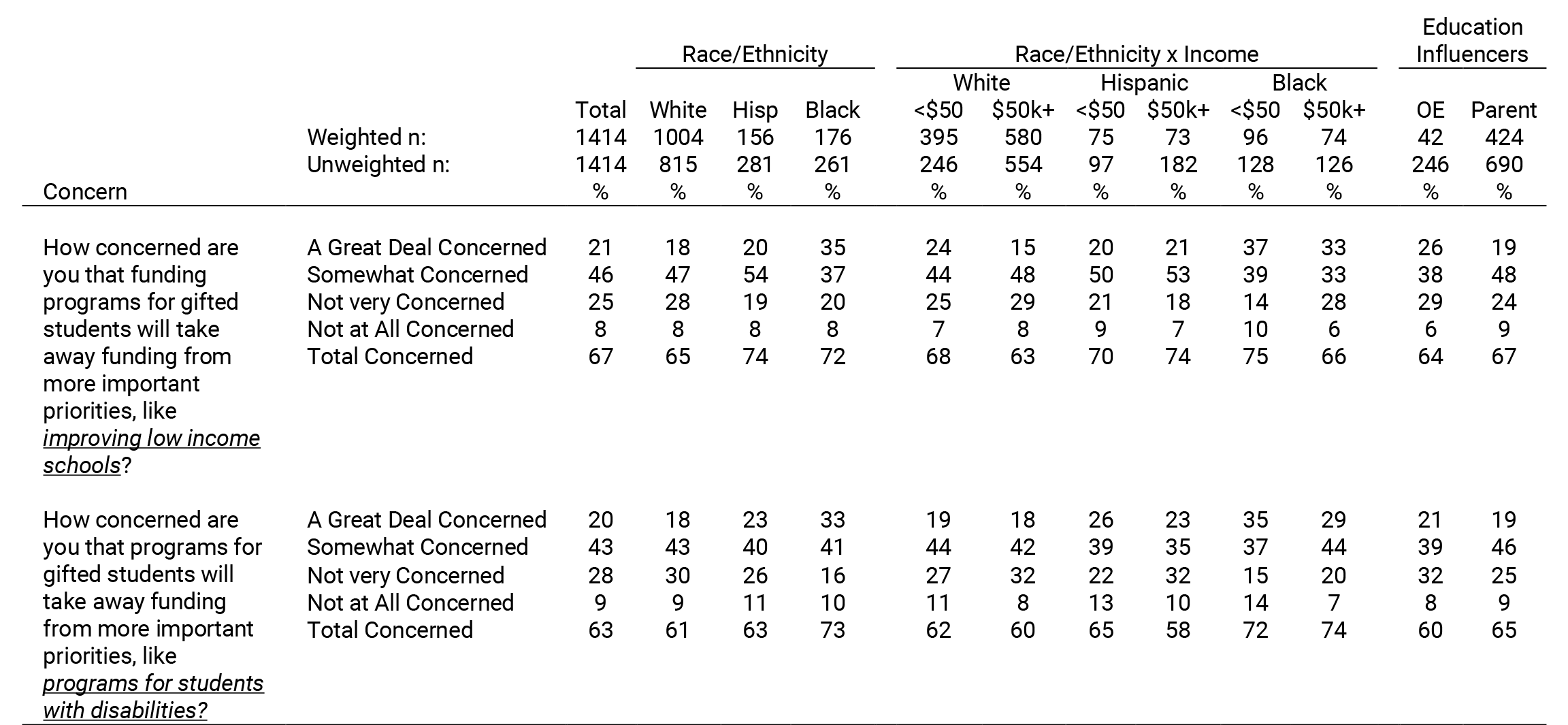

Concern over re-allocation of funds from other programs to support gifted education. Earlier in the poll, respondents made it clear that they had a general dislike of spending trade-offs in education, with 80% regretting the need to choose among different groups of students (see Chapter 2). There was aversion to the fact that funding one program often requires diverting funds from another equally worthy program. However, different constituent groups are likely to favor different kinds of trade-offs. IEA-P respondents were asked two questions which assessed public concern over funding gifted education instead of other programs. The first question assessed concern that gifted education would draw funds away from students with learning disabilities, and the second question assessed concern that gifted education would divert funds from efforts to improve low-income schools.

These were the only questions on the IEA-P where public support for gifted education faltered. In each instance between 60-75% of respondents indicated some level of concern that funds spent on gifted education would take money away from other priorities. Concern tended to be higher for the question which referenced improving low-income schools (Table 3.2).

Education Influencers. Opinion Elites and Parents had nearly identical responses to each question. Among Opinion Elites, 64% indicated concern that funding for gifted programs would be drawn from low-income schools, and 60% indicated concern that funds would be reallocated from programs for students with learning disabilities. Among Parents, 67% expressed concern that funding would be moved from low- income schools, and 65% that it would be moved from students with learning disabilities.

Racial/Ethnic Groups. Nearly three quarters of Hispanic respondents, 74%, indicated concern over the impact of gifted education on funding for low-income schools, and 63% were concerned that gifted education programing would take funds away from students with learning disabilities. Black respondents were far more likely than White or Hispanic respondents to report “A Great Deal” of concern that gifted education would take funds from improvements to low-income schools (35% Black, 18% White, and 20% Hispanic).

Percentage of Respondents’ Concern About Gifted Education Siphoning Funds from Other Programs: Comparing Funds Drawn from Low-Income Schools or from Students with Learning Disabilities (Q42, R9-10).

Notes. = Income under $50,000/year, $50k+ = Income $50,000 and up, OE = Opinion Elite, Hisp = Hispanics, Total Concern = the sum of A Great Deal of Concern plus Somewhat Concerned. At the 95% confidence level the standard error of measure for the entire sample is ±2.51%. It is ±6.21% among Opinion Elites, ±3.73% among Parents, ±6.03% among Blacks, ±5.81% among Hispanics, and ±3.33 among Whites. Race/Ethnicity does not include respondents who selected more than one race. Race/Ethnicity x Income does not include respondents who selected “Prefer Not to Indicate.”

While these findings provide a useful reality check on the context of the public’s support for gifted education, it is worth noting that public concern over teacher preparation for teachers of the gifted (82% concerned), over failure to identify minority and low-income students (84% concerned), and over the absence of gifted programs in low-income areas (81% concerned) far exceeded public concern that gifted programs would cause redirection of funds from high-need students (67% over siphoning from low-income students and 63% from students with learning disabilities). Concern over providing specific improvements in gifted education may override concern over funding distribution across programs if the initial improvements to gifted education target teacher preparation, equitable identification, and program access, so the emphasis is on building capacity, not losing resources.

Win-Win

The public wants no reductions in funding for improvements to low-income schools, and at the same time more funds allocated for gifted programs in high-need areas. Combined, these preferences point to a win-win of opportunity: Building gifted education programs in low- income areas simultaneously increases resources for low-income schools and provides more support for a chronically neglected population of gifted, low-income students.

Synopsis

- Overall, the public was more likely to express concern over specific issues in gifted education than over gifted education generally. While 57% of the public voiced concern over gifted education, 82% were concerned about the availability of quality teachers for gifted students, 84% were concerned about equitable identification of gifted students, and 76% were concerned that gifted students could not accelerate. Advocates may achieve more success if they promote specific program elements in addition to an omnibus “gifted program.”

- The number of people concerned about teacher preparation for teachers of the gifted, about the failure to identify minority and low- income students, and about the absence of gifted programs in low-income areas exceeded the number of people concerned that gifted programs would cause redirection of funds away from other students.

- Concern that teachers are not sufficiently trained to work with gifted students was voiced by 81% of IEA-P respondents. The rate of concern was over 80% for Opinion Elites, Parents, and all racial/ethnic x income groups.

- 77% of the public was concerned that students are grouped in classrooms by age rather than academic ability. The magnitude of the response suggests that even people whose children would not qualify for an advanced class support some form of ability grouping.

- A majority of respondents reported concern over equitable identification and program access. Concern over identification and program access was especially high among Black and Hispanic respondents. However, Black and Hispanic respondents were somewhat more likely to express concern over identification compared to program access. 97% of higher-income Black respondents expressed “A Great Deal” of concern over equitable identification. The reason for the heightened concern about identification is unclear; however, it stands to reason that even nearby programs are inaccessible to some qualified candidates if the identification process is not equitable.

- Concern over availability of schools for gifted students was reported by 77% of IEA-P respondents. Consistent with the public’s support for ability grouping and acceleration, Americans support allowing gifted students to learn with like- minded peers.

References

Bloom, B. S., Madaus, G. F., & Hastings, J. T. (1971). Handbook on Formative and Summative Evaluation of Student Learning . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Public Perception and Professional Practice

Teacher Education is Pivotal to High Quality Gifted Education

The American public intuitively understands what research consistently demonstrates: Teacher preparation is vital to a quality education. This is as true for gifted education as it is for general or special education. Unfortunately, opportunities for pre-service teachers to learn about gifted students are rare. Currently, neither federal nor state requirements for pre-service teacher preparation include learning about gifted students.

After a general education teacher leaves the university, what she learns is a function of personal choice and district priorities; there is no guarantee that she will ever learn how to meet the needs of her gifted students. Some states require general education teachers to receive some form of professional development in gifted education once they are in the classroom, but this requirement is articulated differently from state to state and often from district to district (NAGC, 2015). Archambault et al. (1993) polled almost 4,000 third- and fourth- grade teachers nationwide; 61% of these teachers reported receiving no professional development related to gifted education. In a separate nationwide poll, 1,231 districts reported allocating only 4% of professional development dollars towards topics related to gifted education (Westberg, et al., 1998). Professional development experiences were reported more frequently by school districts in states that had a mandate for gifted education, indicating that policy has an impact on teacher knowledge, and ultimately, on classroom practice.

These statistics suggest that the public is right to be concerned about the absence of teacher preparation to work with gifted students nationwide. The absence of pre-service or in-service teacher education perpetuates common problems gifted students face in the regular classroom, first and foremost, the absence of appropriately challenging differentiation (Reis et al., 2004; Reis, Westberg, Kulikowich, & Purcell, 1998).

Accurate, evidence-based information is crucial to dispelling misconceptions about gifted students and gifted education services; pre-service or in-service education is a primary venue for providing information to educators. When offered, professional development about gifted students and their educational needs has multiple benefits. Lassig (2009) found that teachers’ attitudes towards gifted students were more positive in schools which provided professional development, a finding that echoes an earlier finding that classroom climate and teaching skills both improved after professional development in gifted education (Hansen & Feldhusen, 1994). Dixon and colleagues found that teachers’ sense of self-efficacy increased with the number of hours in professional development related to curriculum differentiation for gifted students (Dixon, Yssel, McConnell, & Hardin, 2014).

The absence of pre-service or in-service teacher education perpetuates common problems gifted students face in the regular classroom.

Because referral for gifted programming often comes from a teacher who has no education about gifted students, it leads to errors and inequities in identification (Elhoweris, 2008; McBee, 2006; Siegle & Powell, 2004). Teacher education is a remedy to this problem. Bianco and Leech (2010) found that twice-exceptional students were more likely to be referred for identification by teachers who had participated in professional development. In separate studies focused on gifted students in low-income settings, Gallagher and Gallagher (2013) and Swanson (2006) each found that providing general education teachers training in gifted child characteristics and advanced teaching methods led to increased identification of students traditionally underrepresented in gifted programs.

Teacher education that is supported by standards and structure tends to yield the best results. For instance, Westberg and Daoust (2003) investigated the efficacy of teacher preparation delivered in-school, in-district, and at university. They found that all teachers were more likely to modify instruction following professional development, but only university study reliably led to significant improvement in teachers’ classroom practices compared to teachers with no training in gifted education. Results of the Westberg and Daoust study suggest that teachers with college or university credentials in gifted education are significantly more likely than teachers with little or no professional development to show improvement making instructional choices for both gifted and general education, in addition to acquiring skills in curriculum modification for the gifted.

Students in both gifted and general education would benefit from a system similar to special education, where: (1) all pre-service teachers learn the fundamentals of gifted education, (2) motivated teachers pursue a specialist license or degree in preparation for more intensive settings (e.g., honors classes, self-contained classrooms), and (3) ongoing in-service professional development provides opportunities for teachers to enhance their skills. Pre-service or in-service education for district and school administrators is also essential, as administrators are often the gatekeepers for programmatic change.

Results of the IEA-P suggest that promoting teacher preparation in gifted education is a viable path for positive change on behalf of gifted students. An overwhelming majority of the American public voiced a desire for quality teachers with the knowledge and skills to work with all their students, including students who are gifted.

References

Archambault, F. X., Westberg, K. L., Brown, S. W., Hallmark, B. W., Zhang, W., & Emmons, C. L. (1993). Classroom practices used with gifted third and fourth grade students. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 16, 103–119.

Bianco, M. Y., & Leech, N. (2010). Twice-exceptional learners: Effects of teacher preparation and disability labels on gifted referrals. Teacher Education and Special Education, 33, 319-334.

Dixon, F. A., Yssel, N., McConnell, J. M., & Hardin, T. (2014). Differentiated instruction, professional development, and teacher efficacy. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 37, 111-127.

Elhoweris, H. (2008). Teacher judgment in identifying gifted/talented students. Multicultural Education, 15(3), 35-38.

Gallagher, S. A., & Gallagher, J. J. (2013). Using Problem-based Learning to explore unseen academic potential. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-based Learning, 7(1), 111-131.

Hansen, J., & Feldhusen, J. F. (1994). Comparison of trained and untrained teachers of the gifted. Gifted Child Quarterly, 38(3), 115-121.

Lassig, C. J. (2009). Teachers’ attitudes towards the gifted: The importance of professional development and school culture. Australasian Journal of Gifted Education, 18(2), 32-42.

McBee, M. T. (2006). A descriptive analysis of referral sources for gifted identification screening by race and socioeconomic status. Journal for Secondary Gifted Education, 17, 103-111.

National Association for Gifted Children (2015).2014-2015 State of the states in gifted education: policy and practice data. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www.nagc.org/sites/default/files/key%20reports/2014-2015%20State%20of%20the%20States%20%28final%29.pdf

Reis, S. M., Gubbins, E. J., Briggs, C., Schreiber, F. R., Richards, S., & Jacobs, J. (2004). Reading instruction for talented readers: Case studies documenting few opportunities for continuous progress. Gifted Child Quarterly, 48, 309-338.

Reis, S. M., Westberg, K. L., Kulikowich, J. M., & Purcell, J. H. (1998). Curriculum compacting and achievement test scores: What does the research say? Gifted Child Quarterly, 42, 123-129.

Swanson, J. D. (2006). Breaking through assumptions about low-income, minority gifted students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 50(1), 11-25.

Siegle, D., & Powell, T. (2004). Exploring teacher bias- es when nominating students for gifted pro- grams. Gifted Child Quarterly, 48(1), 21-29.

Westberg, K.L., Burns, D. E., Gubbins, E. J., Reis, S. M., Park, S. & Maxfield, L. R. (1998). Professional development practices in gifted education: Results of a national survey. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. 424708)

Westberg, K. L., & Daoust, M. E. (2003, Fall). The results of the replication of the classroom practices survey replication in two states. The National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented Newsletter, 3–8.